Editor’s Note: The following comprises the fourth chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER IV

The first thing to be done was to take my wife into Bulawayo, and then return at once with a body of armed men to Essexvale, in order to make a display of force which might deter those natives, who were still sitting quiet watching events, from joining the rebels; for I knew that the general idea was, that there being now no longer any police force in the country, the Government was practically powerless to cope with an organised rebellion. I therefore had all our horses saddled up immediately to be ready for emergencies, and in order to guard against surprise placed George as a vidette on the top of a rise behind the house, from which a good view of the surrounding country was obtainable. Then, whilst we were having breakfast, I sent messengers to summon all the headmen of the kraals in the immediate vicinity of the homestead. These men, I may say, were all in possession of cattle belonging to my Company, and as none of them were pure-blooded Matabele, I imagined they would have no sympathy with the insurgents.

They all answered my summons, accompanied by many of their people, and before leaving I spoke to them, and did my best to impress upon them the folly of rebelling against the white man. They professed themselves in perfect accord with all I said; averred that they were quite content to live with me as their “inkosi,” and protested that they had nothing to hope for from the overthrow of the white man by the Matabele. In conclusion, I told them that I was going into Bulawayo to place my wife in a position of safety, but that I would return immediately with an armed force and endeavour to recover some of the cattle stolen by Gwibu and the rest of the Matabele. Mr. Blöcker wished to remain at the homestead until my return, but this I would not allow, as I did not care to leave a white man all by himself; and besides I required him to help me in getting some men together. George—the colonial Kafir—however, stopped behind, as he considered himself quite safe with Umsetchi’s people,—Umsetchi being the headman of several little kraals close to the house, with the inhabitants of which we had always been on the most friendly terms.

Our ride into Bulawayo was altogether uneventful, as our road lay almost entirely through uninhabited country, and did not cross the line that the rebel natives of the district would have been likely to take on their way to the fastnesses of the Malungwani Hills. As, however, it was a scorching hot day it was a very trying experience for my wife.

Just before reaching town we met Mr. Claude Grenfell, who, with Messrs. Norton and Edmonds, was on his way out to Essexvale with a cart and horses to bring in my wife, and from them we learned that the insurrection was becoming general all over the country, and that forces had already been raised and sent out to relieve miners and settlers in the outlying districts. The Hon. Maurice Gifford had left the previous day for the Insiza, whilst Messrs. Napier and Spreckley were just on the point of starting for other disturbed parts of the country.

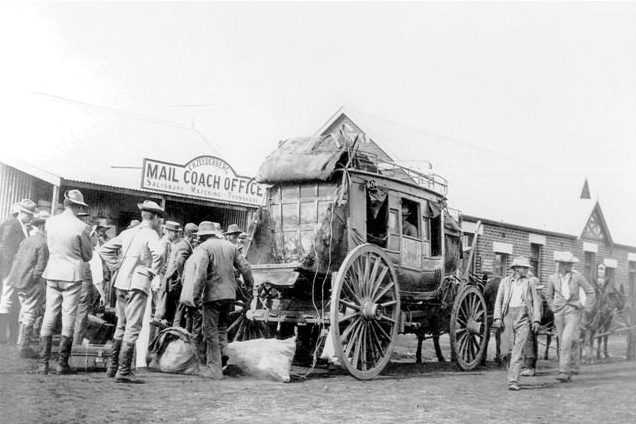

After handing over my wife to the kind care of her good friend Mrs. Spreckley, I at once set to work to get together a mounted force with which to return immediately to Essexvale, and thanks to the energetic assistance of Mr. Blöcker and Mr. Norton I was able to leave Bulawayo again at eight o’clock the same evening with thirty-six mounted men. I had wished to raise a force of 100 men, but found it impossible to do so, nearly all the horses and rifles in the possession of the Government having been given out to equip the forces already sent out before my arrival in town. There were men enough left, and good men too, ready to go with me anywhere, but the Government could only supply six horses—and not good ones at that—and twenty rifles. However, I managed to raise thirty private horses, and some private rifles, and got away about two hours after sundown with a compact little force of thirty-six mounted men.

The moon was now getting near the full, and by its light we pushed on, and at 2 A.M. on Thursday, 26th March, were back at my homestead, which is just twenty-three miles distant from Bulawayo. Here I found everything as I had left it, George having installed himself with some of Umsetchi’s men in the stable, which being built very solidly of stone, they might easily have held against any ordinary attack.

I had left Essexvale a few hours before, without any very bitter feeling against the Kafirs, for after all, looking at things from their point of view, if they thought they could succeed in shaking off the white man’s rule, and retaking all the cattle that once were theirs or their king’s, and all those brought into the country since the war as well, why shouldn’t they try the chances of rebellion? I knew they would have to fight to accomplish their ends, and it was for them to consider whether the game was worth the candle or not. At that time, however, I was far from realising what had happened, and was inclined to judge the Kafirs very leniently. But my visit to Bulawayo had changed my sentiments entirely, and the accounts which I had there heard of the cruel and treacherous murders that had been perpetrated on defenceless women and children, besides at once destroying whatever sympathy I may have at first felt for the rebels, had not only filled me with indignation, but had excited a desire for vengeance, which could only be satisfied by a personal and active participation in the killing of the murderers. I don’t defend such feelings, nor deny that they are vile and brutal when viewed from a high moral standpoint; only I would say to the highly moral critic, Be charitable if you have not yourself lived through similar experiences; be not too harsh in your judgment of your fellow-man, for you probably know not your own nature, nor are you capable of analysing passions which can only be understood by those Europeans who have lived through a native rising, in which women and children of their race have been barbarously murdered by savages; by beings whom, in their hearts, they despise; as rightly or wrongly they consider that they belong to a lower type of the human family than themselves.

I offer no opinion upon this sentiment, but I say that it undoubtedly exists, and must always aggravate the savagery of a conflict between the two races; whilst the murder of white women and children, by natives, seems to the colonist not merely a crime, but a sacrilege, and calls forth all the latent ferocity of the more civilised race. For, kind and considerate though any European may be under ordinary circumstances to the savages amongst whom he happens to be living, yet deep down in his heart, whether he be a miner or a missionary, is the conviction that the black man belongs to a lower type of humanity than the white; and if this is a mistaken conviction, ask the negrophilist who professes to think so, whether he would give his daughter in marriage to a negro, and if not, why not?

At any rate the lovers and admirers of the Matabele would do well to caution their protégés not to commence another insurrection by the murder of white women and children, for should they do so, they will once more have cause to rue a war of retaliation, that will be waged with all the merciless ferocity which must inevitably follow upon such a course; as, although the murder of Europeans by savages may commend itself to certain arm-chair philosophers in England, who can see no good in a colonist, nor any harm in a savage, yet the colonists themselves cannot look upon such matters from the same point of view, and will take such steps to prevent the recurrence of any farther ebullitions of temper, as were taken by the United States troops after the massacres of Minnesota, or by the British troops at Secunderabad and other places in suppressing the Indian Mutiny.

Before resuming my personal narrative, I will give a short account of what had already taken place in the progress of the insurrection on Essexvale itself, and in those parts of the Insiza and Filibusi districts which border upon Essexvale.

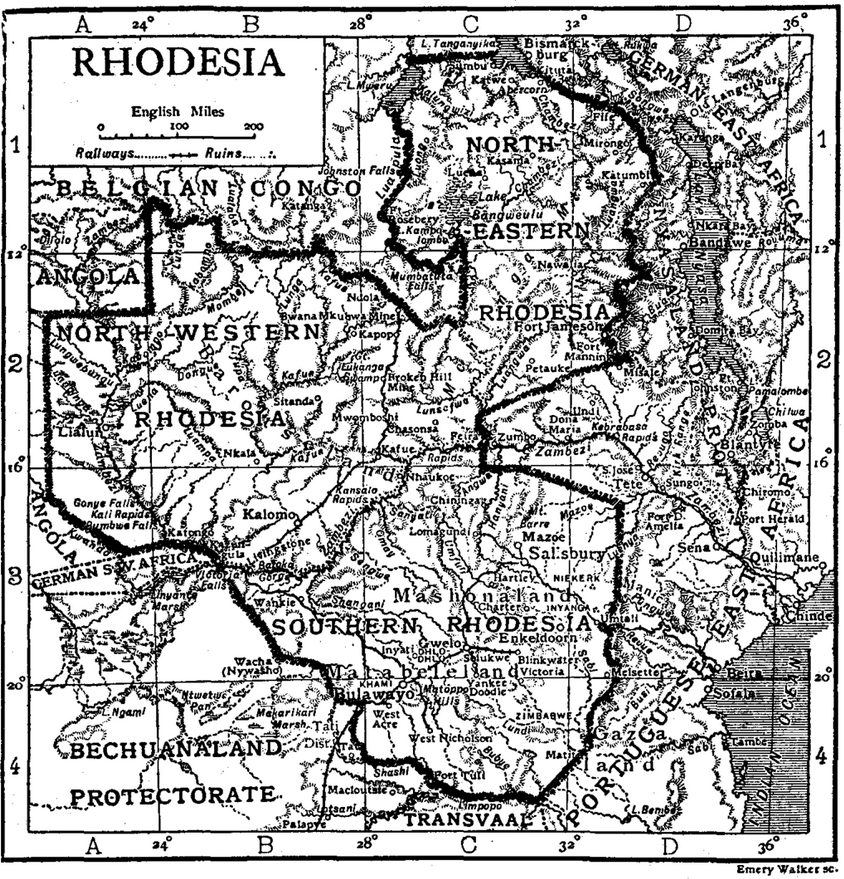

There is reason to believe that the outbreak of the rebellion, commencing as it did with the murder of a native policeman on Friday, 20th March, was somewhat premature, and thus there was an interval of nearly three days between the date of this murder and the day when the first white men were killed by the natives. From the Umzingwani, the flame of rebellion spread through the Filibusi and Insiza districts, to the Tchangani and Inyati, and thence to the mining camps in the neighbourhood of the Gwelo and Ingwenia rivers, and indeed throughout the country wherever white men, women, and children could be taken by surprise and murdered either singly or in small parties; and so quickly was this cruel work accomplished, that although it was only on 23rd March that the first Europeans were murdered, there is reason to believe that by the evening of the 30th not a white man was left alive in the outlying districts of Matabeleland. Between these two dates many people escaped or were brought in to Bulawayo by relief parties, but a large number were cruelly and treacherously murdered.