Editor’s Note: The following comprises the second chapter of Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia, by Frederick Courteney Selous (published 1896). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER II

Of our life on Essexvale I have but little of interest to relate. In September and October the weather became intensely hot, but our well-thatched house we found to be much cooler than any building in Bulawayo, to which seat of light and learning we paid but occasional visits. Our wire-wove house did not arrive in Matabeleland until late in November, just as the rainy season was setting in, and it was not until towards the end of the year that it was put together and stood ready to receive us, on the site I had chosen for it. This was a very picturesque position on the top of a cliff about eighty feet above the Ingnaima river. Here we lived happily and contentedly for three months, and were apparently on the most friendly terms with all the natives living near us. Our Company bought about 1200 head of cattle, and these I distributed amongst the natives living on Essexvale—an estate of nearly 200,000 acres—to herd for us in lots of from ten to thirty in number, which they were very glad to do for the sake of the milk. To all the headmen living immediately round the homestead I gave a larger proportion of milk cows, on the condition that they brought me daily half the milk.

I was assisted in the management of the estate by a young German, Herr Blöcker, who had taken his diplomas in a German School of Forestry, as it was part of our Company’s scheme to start a plantation of gum trees, the timber of which is valuable for mining purposes. We therefore cleared and ploughed up about forty acres of land, and planted out over 5000 trees raised from seed on a strip of eight acres near the house. The rest of the ploughed land we sowed with maize, reserving about an acre near the river for a vegetable garden. The ground round the house my wife laid out in flower-beds, and I had also beds prepared for the planting of orange and other fruit trees, which I had ordered from the Cape Colony; whilst several banana and grenadilla plants, which had been given us by the Rev. Mr. Helm, were already growing well. Altogether, in spite of the most unseasonable drought which prevailed during January, February, and March, our homestead commenced to look quite pretty, and another year’s work would have made a nice place of it; whilst the view from our front door up the river, with our cattle and horses grazing on the banks, and ducks and geese swimming in the pools or sunning themselves on the sand, was always singularly homelike.

As I have said above, up to the day of the native insurrection, which broke out towards the end of March, all the natives on Essexvale appeared to be on the most friendly terms with us, and were always most civil and polite to my wife, who had grown to like them very much. We had done them many good turns, and I believe they liked us as individuals. Umlugulu, a relation of Lo Bengula’s, and one of the principal men in that king’s time, as well as a high priest of the ceremonies at the annual religious dance of the Inxwala, was living about fifteen miles away, and often came to see us. He was a very gentle-mannered savage, and always most courteous and polite in his bearing, and by us he was always treated with the consideration due to one who had held a high position and been a man of importance in Lo Bengula’s time. It is now supposed, and I think with justice, that this man was one of the chief instigators of the rebellion; but if this is so, I have strong reasons for believing that he only finally made up his mind that the time had come for the attempt to be made to drive the white men out of the country when he learnt that the whole of the police force of Matabeleland, together with the artillery, munitions of war, etc., which had been taken down to the Transvaal by Dr. Jameson, had been captured by the Boers. My reason for thinking so is, that before he heard this news he asked me several times to take some unbranded cattle from him, and have them herded amongst my own, or bought from him at my own price. This request I could not grant, but advised him to go and tell Dr. Jameson the story he had told me, as to how these cattle came to be in his possession without the Company’s brand on them. After he heard the news of Dr. Jameson’s surrender, Umlugulu never said anything more about these cattle, but he often came to see me, and always questioned me very closely as to what had actually happened in the Transvaal. Although at that time I had no idea as to the lines on which I now think his mind was working, I gave him little or no information, the more so that I could see he was very anxious to get at the truth.

Towards the end of February, Mr. Jackson, the native commissioner in my district, who was living with a sub-inspector and a force of native police at a spot on one of the roads through Essexvale about twelve miles distant from our house, informed me that rumours of coming disaster to the white man, purporting to emanate from the “Umlimo” or god of the Makalakas, who dwells in a cave of the Matopo Hills, were being spread abroad amongst the people of Matabeleland. Shortly before this there had been a total eclipse of the moon. This the Umlimo told the natives meant that white man’s blood was about to be spilt. Further than this, they were informed that Lo Bengula was not dead, but was now on his way back to Matabeleland with a large army from the north, whilst two other armies were coming to help him against the white man from the west and east. “Watch the coming moon,” said the Umlimo, “and be ready.” He also claimed to have sent the rinderpest, which had just reached the cattle in the north of Matabeleland—though of what advantage that scourge was to the natives I don’t quite see—and promised that he would soon afflict the white men themselves with some equally terrible disease.

Now, although these rumours of a native rising were current in Matabeleland some time before the insurrection actually broke out, and were reported to the then acting chief native commissioner, Mr. Thomas, and to the heads of the Government, I do not think that they would have been warranted in taking any steps of a suppressive nature at this juncture; for there was absolutely nothing tangible to go upon, nor could any commission of inquiry have come to any other conclusion than that the natives had no intention of rebelling; for they were as quiet and submissive in their demeanour towards Europeans as they ever had been since the war, and there was absolutely no evidence of any secret arming amongst them; and the fact remains that, with one exception, all those Europeans in Matabeleland who had had a long experience of natives—that is, the native commissioners, missionaries, and a few old traders and hunters, amongst whom I must include myself—were unanimous in the opinion that no rebellion on the part of the Matabele was to be apprehended. I say there was one exception, as I have been told that Mr. Usher, an old trader long resident in Matabeleland, and who since the first war has been living altogether amongst the natives, has always maintained that the Matabele would one day rise against the white man.

For myself, I had many conversations with Mr. Jackson on the subject, and we came to the conclusion, after talking with several intelligent natives regarding the rumours going about, that the Matabele were not likely to rebel until Lo Bengula appeared with his army. “However,” said Mr. Jackson one evening, “it is very difficult to worm a secret out of a native, and if there should be an insurrection those are the devils we have to fear,” pointing to his squad of native Matabele policemen, sitting about round their huts all armed with repeating Winchester rifles. At that time no one would have imagined that these native policemen—all fine, active-looking young fellows, and very smart at their drill—would have been likely to mutiny, since they were not only very well disciplined but most civil and obedient to their white officers; whilst, on the other hand, they were constantly at loggerheads with their compatriots, whom they had to bring to book for any transgression of the Chartered Company’s laws, and more particularly for evasion of the regulations exacting a certain amount of labour annually at a fixed rate of pay from every able-bodied young man. However, as subsequent events have shown, Mr. Jackson was right in his prognostication, for when the rebellion did break out, about half the native police at once turned their rifles against their employers. The remainder were true to their salt, but had to be disarmed as a precautionary measure.

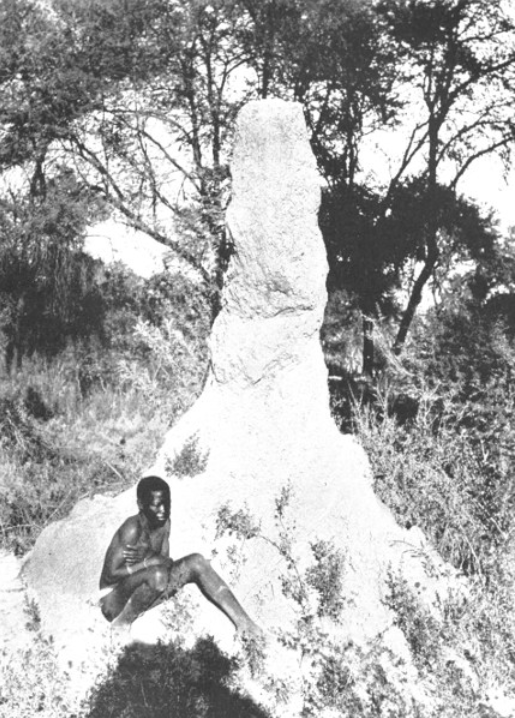

I will now before going further say a word concerning the “Umlimo” or god of the Makalakas, who has apparently played such an important part in the present rebellion, but who, I think, has in reality only been the instrument employed by the actual leaders of the insurrection to work upon the superstitions of the people, and mould them to their will. To the best of my belief, there exists amongst the Makalakas, as amongst all the tribes of allied race throughout South-Eastern Africa, an hereditary priesthood, confined to one family, though from time to time certain other young men are adopted by the high priest and initiated into the mysteries of his profession. These men in common with the actual sons of the high priest are known henceforth as children of the god. The head of the family lives in the Matopo Hills, and is known as the Umlimo, but as far as one can understand from the rather conflicting statements made concerning him by the natives, he is not actually the Umlimo, but a being possessed of all the ordinary attributes of man,—in fact a human being, with a spiritual nature superadded which enables him to commune with the unseen Deity that pervades space, and communicate the wishes or commands of the invisible spirit to the people. The temple of the Umlimo is a cave in the Matopo Hills, whither the people repair to consult him; and I believe that the voice which is heard in answer to their questions from the depths of the cave is supposed to emanate not from the human Umlimo or priest, but to be the actual utterance of the invisible god. The human Umlimo is kept wonderfully well posted up concerning everything that happens in Matabeleland, probably by the various members of his family, who live in different parts of the country, and who often visit him. He is thus often enabled to make very shrewd answers to the questions asked him, and to show himself conversant with matters which his interlocutors thought were known only to themselves; and in this way he has gained a great ascendency over the minds of the people.

If one asks who the Umlimo is, the answer is that he is a spirit or supernatural being of infinite wisdom, known to man only as a voice speaking from the depths of a cave. He is said to be able to speak all languages, as well as to be possessed of the faculty of roaring like a lion, crowing like a cock, barking like a dog, etc. On the other hand, the human Umlimo accepts or rather demands presents from those who visit his cave for the purpose of consulting the Deity, and possesses not only cattle, sheep, and goats, but also a large number of wives. The great mass of the Matabele people seem to me to have very vague ideas concerning the Umlimo; and sometimes I think that besides the priest in the Matopos through whom the voice of God is supposed to be heard, there are other priests, or so-called Umlimos, in other parts of the country through whom they believe that the commands of the Almighty can be conveyed to them. At any rate, both prior to and during the present rebellion, utterances purporting to emanate from the “Umlimo” have been implicitly believed in, and the commands attributed to him obeyed with a blind fanaticism, that one would not have looked for in a people who always seem to be extremely matter of fact and practical in everyday life. It may seem strange that this “Umlimo,” or god of the despised Makalakas, should be accepted as an oracle by the Matabele, but I know that Lo Bengula professed a strong belief in his magical powers, and from time to time consulted him. I believe, however, that the Umlimo was made use of for the purposes of the present rebellion by Umlugulu, and other members of the late king’s family.

These men were naturally not content with their position under the white man’s rule, and as ever since the war they had probably been rebels at heart, they only wanted an opportunity to call the people to arms. This opportunity they thought had come when they heard that the entire police force of Matabeleland, together with most of the big guns and munitions of war up till then stored in Bulawayo, had been captured by the Boers. For to them the police represented the fighting or military element amongst the white men, and they more or less despised all other classes, whom they usually saw going about altogether unarmed and defenceless. When the police were gone, therefore, they at once probably set about stirring up a rebellion, and got the Umlimo to play their game and work upon the superstitions of the people. This at any rate is my own opinion of the origin of the insurrection.

About the middle of March I was appointed cattle inspector for the district between the Umzingwani and Insiza rivers, and had to do a lot of riding about in my endeavours to assist the Government to arrest the spread of the rinderpest. However, one might as well have tried to stop a rising tide on the sea-shore, as prevent this dreadful disease from travelling steadily down the main roads, leaving nothing but rotting carcasses and ruined men behind it. Therefore, while still strictly prohibiting all movement of cattle from infected districts to parts of the country yet free from the terrible scourge, the Government declared the main roads open for traffic on Tuesday, 24th March, in order that as many waggon-loads of provisions as possible might be brought into Bulawayo, whilst any oxen were still left alive to pull them; for at this time the only calamities apprehended in Matabeleland were famine, and the complete dislocation of transport throughout the country owing to the terrible mortality amongst the cattle from rinderpest. These dangers indeed seemed so pressing that the Government was called upon by a deputation from the Chamber of Commerce to at once purchase 2000 mules, to be used for the importation of food-stuffs into Bulawayo, and their distribution from that centre to the various mining districts.

On Sunday, 22nd March, I reached Bulawayo late in the evening, after a very long day’s ride inspecting cattle, and I then heard rumours of a disturbance having taken place between some of Mr. Jackson’s native police and the inhabitants of a Matabele kraal near the north-western boundary of our Company’s property of Essexvale. On the following day I got a fresh horse and rode twenty-five miles down the Tuli road to Dawson’s store on the Umzingwani river—the limit of my beat in this direction—issuing passes to all the waggons I met with to proceed on their way up or down the road on the following morning. Arrived at the store, I there met my friend Mr. Jackson, the native commissioner, and Mr. Cooke, and learned from them that a native policeman had been murdered by the Matabele on the previous Friday night, and that the murderers had fled into the Matopo Hills, taking all their women and children as well as their cattle with them. My friends were only waiting for a detachment of native police, under two white inspectors, to follow up the murderers and endeavour to bring them to justice.