Editor’s note: Here follow Chapters 13 through 20 of My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, by General Ben Viljoen (published 1902). All spelling in the original.

CHAPTER XIII

DRIVEN FROM THE BIGGARSBERGEN.

We spent the next few weeks in entrenching and fortifying our new positions. General Botha had left with some men for the Orange Free State which Lord Roberts, having relieved Kimberley, was marching through. General Joubert died about this time at Pretoria, having been twenty-one years Commandant-General of the South African Republic. He was without doubt one of the most prominent figures in the South African drama.

General Botha now took up the chief command and soon proved himself to be worthy of holding the reins. He enjoyed the confidence and esteem of our whole army, a very important advantage under our trying circumstances.

Assisted by De Wet he was soon engaged in organizing the commandos in the Orange Free State, and in attempting to make some sort of a stand against the British, who were now marching through the country in overwhelming numbers. In this Republic the burghers had been under the command of the aged General Prinsloo, who now, however, had become so downhearted that the supreme command was taken from him and given to General De Wet. Prinsloo surrendered soon after, in doing which he did his people his greatest service; it was, however, unfortunate that he should have succeeded in leading with him 900 burghers into the hands of the enemy.

In the Biggarsbergen we had nothing to do but to sleep and eat and drink. On two separate occasions, however, we were ordered to join others in attacking the enemy’s camp at Elandslaagte. This was done with much ado, but I would rather say nothing about the way in which the attacks were directed. It suffices to say that both failed miserably, and we were forced to retire considerably quicker than we had come.

Our generals, meantime, were very busy issuing innumerable circulars to the different commandos. It is impossible for me to remember the contents of all these curious manifestos, but one read as follows:—

“A roll-call of all burghers is to be taken daily; weekly reports are to be sent to headquarters of each separate commando, and the minimum number of burghers making up a field-cornetship is therein to be stated. Every 15 men forming a field-cornetship are to be under a corporal; and these corporals are to hold a roll-call every day, and to send in weekly detailed reports of their men to the Field-Cornet and Commandant, who in his turn must report to the General.”

Another lengthy circular had full instructions and regulations for the granting of “leave” to burghers, an intricate arrangement which gave officers a considerable amount of trouble. The scheme was known as the “furlough system,” and was an effort to introduce a show of organisation into the weighty matter of granting leave of absence. It failed, however, completely to have its desired effect. It provided that one-tenth of each commando should be granted furlough for a fortnight, and then return to allow another tenth part to go in its turn. In a case of sick leave, a doctor’s certificate was required, which had to bear the counter-signature of the field-cornet; its possessor was then allowed to go home instead of to the hospital. Further, a percentage of the farmers were allowed from time to time to go home and attend to pressing matters of their farms, such as harvesting, shearing sheep, etc. Men were chosen by the farmers to go and attend to matters not only for themselves but for other farmers in their districts as well. The net result of all this was that when everybody who could on some pretext or other obtain furlough had done so, about a third of each commando was missing. My burghers who were mostly men from the Witwatersrand Goldfields, could of course obtain no leave for farming purposes; and great dissatisfaction prevailed. I was inundated with complaints about their unfair treatment in this respect and only settled matters with considerable trouble.

I agree that this matter had to be regulated somehow, and I do not blame the authorities for their inability to cope with the difficulty. It seemed a great pity, however, that the commandos should be weakened so much and that the fighting spirit should be destroyed in this fashion. Of course it was our first big war and our arrangements were naturally of a very primitive character.

It was the beginning of May before our friends the enemy at Ladysmith and Elandslaagte began to show some signs of activity. We discovered unmistakable signs that some big forward movement was in progress, but we could not discover on which point the attack was to be directed. Buller and his men were marching on the road along Vantondersnek, and I scented heavy fighting for us again. I gathered a strong patrol and started out to reconnoitre the position. We found that the enemy had pitched their camp past Waschbank in great force, and were sending out detachments in an easterly direction. From this I concluded that they did not propose going through Vantondersnek, but that they intended to attack our left flank at Helpmakaar. This seemed to me, at any rate, to be General Buller’s safest plan.

Helpmakaar was east of my position; it is a little village elbowed in a pass in the Biggarsbergen. By taking this point one could hold the key to our entire extended line of defence, as was subsequently only too clearly shown. I pointed this out to some of our generals, but a commandant’s opinion did not weigh much just then; nor was any notice taken of a similar warning from Commandant Christian Botha, who held a position close to mine with the Swaziland burghers.

We had repeated skirmishes with the English outposts during our scouting expeditions, and on one occasion we suddenly encountered a score of men of the South African Light Horse.

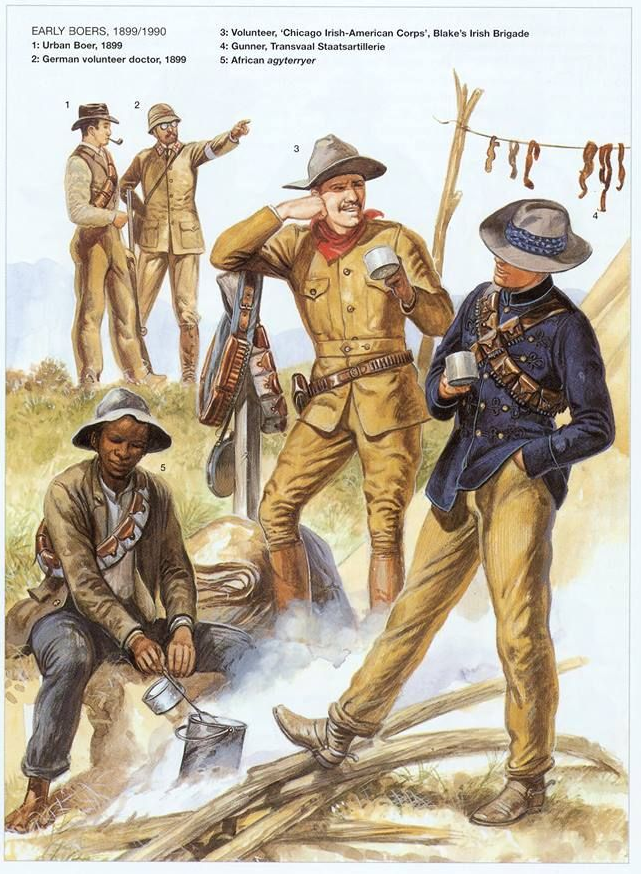

We noticed them in a “donk” (a hollow place) thickly covered with trees and bushes, but not before we were right amongst them. It appears they mistook us for Englishmen, while we thought at first they were members of Colonel Blake’s Irish Brigade. Many of them shook hands with us, and a burgher named Vivian Cogell asked them in Dutch: “How are you, boys?”

To which an Englishman, who understood a little Dutch, answered: “Oh, all right; where do you come from?”

Vivian replied: “From Viljoen’s commando; we are scouting.”

Then the Englishman discovered who we were, but Vivian gave the man no time for reflection. Riding up to him, he asked: “What regiment do you belong to?”

“To the South African Light Horse,” answered the Englishman.

“Hands up!” retorted Vivian, and the English-Afrikander threw down his gun and put up his hands.

“Hands up! Hands up!” was the cry now universally heard, and although a few escaped, the majority were disarmed and made prisoners. It had been made a rule that when a burgher captured a British soldier he should be allowed to conduct him to Pretoria, where he could then obtain a few days’ leave to visit his family. This did much to encourage our burghers to make prisoners, although many lost their lives in attempting to do so.

The next day, General Buller marched on Helpmakaar, passing close to our position. We fired a few shots from our Creusot gun, and had several light skirmishes. The enemy, however, concentrated the fire of a few batteries on us, and our guns were soon silenced.

General L. Meyer had arrived with some reinforcements close to Helpmakaar, but the position had never been strengthened, and the sole defending force consisted of the Piet Retief burghers, known as the “Piet Retreaters,” together with a small German corps. The result was easy to predict. The attack was made, and we lost the position without seriously attempting to defend it. Buller was now, therefore, in possession of the key to the Boer position in Natal, a position which we had occupied for two months—and could therefore, have fortified to perfection—and whose strategic importance should have been known in its smallest details. I think our generals, who had a sufficient force at their disposal, of which the mobility has become world-famed, should have been able to prevent such a fiasco as our occupation of the splendid line of defence in the Biggarsbergen turned out to be.

Here, for the first time in the war, General Buller utilised his success, and followed up our men as they were retreating on Dundee. He descended by the main waggon track from Helpmakaar, and drove the commandos like sheep before him. I myself was obliged to move away in hot haste and join the general retreat. Once or twice our men attempted to make a stand, but with little success.

When we reached Dundee the enemy gradually slackened off pursuit, and at dark we were clear of them. Satisfied with their previous day’s success, and sadly hampered by their enormous convoys, the English now allowed us to move on at our leisure.

CHAPTER XIV

DISPIRITED AND DEMORALISED.

Our first intention was to proceed to Vereeniging, there to join General Botha’s forces. At Klip River Station, that preceding Vereeniging, I was ordered, however, to leave my carts behind and proceed with my men to Vaalbank, as the enemy were advancing with forced marches, and had compelled all the other commandos to fall back on Vereeniging.

On our way we met groups of retreating burghers, each of whom gave us a different version of the position. Some said that the enemy had already swept past Vereeniging, others that they could not now be stopped until they reached Johannesburg. Further on, we had the good fortune to encounter General Botha and his staff. The General ordered me to take up a position at the Gatsrand, near the Nek at Pharaohsfontein, as the British, having split their forces up into two parts, would send one portion to cross the Vaal River at Lindeque’s Drift, whilst the other detachments would follow the railway past Vereeniging. Generals Lemmer and Grobler were already posted at the Gatsrand to obstruct the enemy’s progress.

I asked General Botha how we stood. He sighed, and answered: “If only the burghers would fight we could stop them easily enough; but I cannot get a single burgher to start fighting. I hope their running mood will soon change into a fighting mood. You keep your spirits up, and let us do our duty.”

“All right, General,” I answered, and we shook hands heartily.

We rode on through the evening and at midnight halted at a farm to give our horses rest and fodder. The owner of the farm was absent on duty, and his family had been left behind. On our approach the women-folk, mistaking us for Englishmen, were terrified out of their wits. Remembering the atrocities and horrors committed in Natal on the advance of the Imperial troops, they awaited the coming of the English with the greatest terror. On the approach of the enemy many women and children forsook their homes and wandered about in caves and woods for days, exposed to every privation and inclemency of the weather, and to the attacks of wandering bands of plundering kaffirs.

Mrs. van der Merwe, whom we met here, was exceedingly kind to us, and gave us plenty of fodder for our horses. We purchased some sheep, and slaughtered them and enjoyed a good meal before sunrise; and each one of us bore away a good-sized piece of mutton as provisions for the future.

Our scouts, whom we had despatched over night, informed us that Generals Lemmer and Grobler had taken up their stand to the right of Pharaohsfontein in the Gatsrand, and that the English were approaching in enormous force.

By nine in the morning we had taken up our positions, and at noon the enemy came in sight. Our commando had been considerably reduced, as many burghers, finding themselves near their homes, had applied for twenty-four hours’ leave, which had been granted in order to allow them to arrange matters before the advance of the English on their farms made it impossible. A few also had deserted for the time being, unable to resist the temptation of visiting their families in the neighbourhood.

Some old burghers approached us and hailed us with the usual “Morning, boys! Which commando do you belong to?”

“Viljoen’s.”

“We would like to see your Commandant,” they answered.

Presenting myself, I asked: “Who are you, and where do you come from, and where are you going to?”

They answered: “We are scouts of General Lemmer and we came to see who is holding this position.”

“But surely General Lemmer knows that I am here?”

“Very probably,” they replied, “but we wanted to know for ourselves; we thought we might find some of our friends amongst you. You come from Natal, don’t you?”

“Yes,” I answered sadly. “We have come to reinforce the others, but I fear we can be of little use. It seems to me that it will be here as it was in Natal; all running and no fighting.”

“Alas!” they said, “the Free Staters will not remain in one position, and we must admit the Transvaalers are also very disheartened. However, if the British once cross our frontiers you will find that the burghers will fight to the bitter end.”

Consoled by this pretty promise we made up our minds to do our best, but our outposts presently brought word that the British were bearing to the right and nearing General Grobler’s position, and had passed round that of General Lemmer. Whilst they attacked General Grobler’s we attacked their flank, but we could not do much damage, as we were without guns. Soon after the enemy directed a heavy artillery fire on us, to which we, being on flat ground, found ourselves dangerously exposed.

Towards evening the enemy were in possession of General Grobler’s position, and were passing over the Gatsrand, leaving us behind. I ordered my commando to fall back on Klipriversberg, while I rode away with some adjutants to attempt to put myself in communication with the other commandos.

The night was dark and cloudy, which rendered it somewhat difficult for us to move about in safety. We occasionally fell into ditches and trenches, and had much trouble with barbed wire. However, we finally fell in with General Lemmer’s rearguard, who informed us that the enemy, after having overcome the feeble resistance of General Grobler, had proceeded north, and all the burghers were retreating in haste before them.

We rode on past the enemy to find General Grobler and what his plans were. We rode quite close to the English camp, as we knew that they seldom posted sentries far from their tents. On this occasion, however, they had placed a guard in an old “klipkraal,” for them a prodigious distance from their camp, and a “Tommy” hailed us from the darkness.—

“Halt, who goes there?”

I replied “Friend,” whereupon the guileless soldier answered:

“Pass, friend, all’s well.”

I had my doubts, however. He might be a Boer outpost anxious to ascertain if we were Englishmen. Afraid to ride into ambush of my own men, I called out in Dutch:

“Whose men are you?”

The Tommy lost his temper at being kept awake so long and retorted testily, “I can’t understand your beastly Dutch; come here and be recognized.” But we did not wait for identification, and I rode off shouting back “Thanks, my compliments to General French, and tell him that his outposts are asleep.”

This was too much for the “Tommy” and his friends, who answered with a volley of rifle fire, which was taken up by the whole line of British outposts. No harm was done, however, and we soon rode out of range. I gave up looking for General Grobler, and on the following morning rejoined my men at Klipriversberg.

It was by no means easy to find out the exact position of affairs. Our scouts reported that the enemy’s left wing, having broken through General Grobler’s position, were now marching along Van Wijk’s Rust. I could, however, obtain no definite information regarding the right wing, nor could I discover the General under whose orders I was to place myself. General Lemmer, moreover, was suffering from an acute disease of the kidneys, which had compelled him to hand over his command to Commandant Gravett, who had proved himself an excellent officer.

General Grobler had lost the majority of his men, or what was more likely the case, they had lost him. He declared that he was unaware of General Botha’s or Mr. Kruger’s plans, and that it was absurd to keep running away, but he clearly did not feel equal to any more fighting, although he had not the moral courage to openly say so. From this point this gentleman did no further service to his country, and was shortly afterwards dismissed. The reader will now gather an idea of the enormous change which had come over our troops. Six months before they had been cheerful and gay, confident of the ultimate success of their cause; now they were downhearted and in the lowest of spirits. I must admit that in this our officers were no exception.

Those were dark days for us. Now began the real fighting, and this under the most difficult and distressing circumstances; and I think that if our leaders could have had a glimpse of the difficulties and hardships that were before us, they would not have had the courage to proceed any further in the struggle.

Early next morning (the 29th May, 1900) we reached Klipspruit, and found there several other commandos placed in extended order all the way up to Doornkop.

Amongst them was that of General De la Rey, who had come from the Western frontier of our Republic, and that of General Snyman, whom I regard as the real defender and reliever of Mafeking, for he was afraid to attack a garrison of 1,000 men with twice that number of burghers.

Before having had time to properly fortify our position we were attacked on the right flank by General French’s cavalry, while the left flank had to resist a strong opposing force of cavalry. Both attacks were successfully repulsed, as well as a third in the centre of our fighting line.

The British now marched on Doornkop, their real object of attack being our extreme right wing, but they made a feint on our left. Our line of defence was very extended and weakened by the removal of a body of men who had been sent to Natal Spruit to stop the other body of the enemy from forcing its way along the railway line and cutting off our retreat to Pretoria.

The battle lasted till sunset, and was especially fierce on our right, where the Krugersdorpers stood. Early in the evening our right wing had to yield to an overwhelming force, and during the night all the commandos had to fall back. My commando, which should have consisted of about 450 men, only numbered 65 during this engagement; our losses were two men killed. I was also slightly wounded in the thigh by a piece of shell, but I had no time to attend such matters, as we had to retire in haste, and the wound soon healed.

The next day our forces were again in full retreat to Pretoria, where I understood we were to make a desperate stand. About seven o’clock we passed through Fordsburg, a suburb of Johannesburg.

We had been warned not to enter Johannesburg, as Dr. Krause, who had taken from me the command of the town, had already surrendered it to Lord Roberts, who might shell it if he found commandos were there. Our larger commissariat had proceeded to Pretoria, but we wanted several articles of food, and strange to say the commissariat official at Johannesburg would not give us anything for fear of incurring Lord Roberts’ displeasure!

I was very angry; the enemy were not actually in possession of the town, and I therefore should have been consulted in the matter; but these irresponsible officials even refused to grant us the necessaries of life!

At this time there was a strong movement on foot to blow up the principal mines about Johannesburg, and an irresponsible young person named Antonie Kock had placed himself at the head of a confederacy with this object in view. But thanks to the explicit orders of General L. Botha, which were faithfully carried out by Dr. Krause, Kock’s plan was fortunately frustrated, and I fully agree with Botha that it would have been most impolitic to have allowed this destruction. I often wished afterwards, however, that the British military authorities had shown as much consideration for our property.

We had to have food in any case, and as the official hesitated to supply us we helped ourselves from the Government Stores, and proceeded to the capital. The roads to Pretoria were crowded with men, guns, and vehicles of every description, and despondency and despair were plainly visible on every human face.

CHAPTER XV

OCCUPATION OF PRETORIA.

The enemy naturally profited by our confusion to pursue us more closely than before. The prospect before us was a sad one, and we asked ourselves, “What is to be the end of all this, and what is to become of our poor people? Shall we be able to prolong the struggle, and for how long?”

But no prolongation of the struggle appeared to have entered into our enemy’s minds, who evidently thought that the War had now come upon its last stage, and they were as elated as we were downhearted. They made certain that the Boer was completely vanquished, and his resistance effectually put an end to. At this juncture Conan Doyle, after pointing out what glorious liberty and progress would fall to the Boers’ lot under the British flag, wrote:—

“When that is learned it may happen that they will come to date a happier life and a wider liberty from that 5th of June which saw the symbol of their nation pass for ever from the ensigns of the world.”

Thus, not only did Lord Roberts announce to the world that “the War was now practically over,” but Conan Doyle did not hesitate to say the same in more eloquent style.

How England utterly under-estimated the determination of the Boers, subsequent events have plainly proved. It is equally plain that we ourselves did not know the strength of our resolution, when one takes into account the pessimism and despair that weighed us down in those dark days; and as the Union Jack was flying over our Government buildings we might have exclaimed:

— “England, we do not know our strength, but you know it still less!”

Nearly all the commandos were now in the neighbourhood of Pretoria, General Botha forming a rearguard, and we determined to defend the capital as well as we could. But at this juncture some Boer officer was said to have received a communication from the Government, informing us that they had decided not to defend the town. A cyclist was taking this communication round to the different commandos, but the Commandant-General did not seem to be aware of it, and we tried in vain to find him so as to discover what his plans were. The greatest confusion naturally prevailed, and as all the generals gave different orders, no one knew what was going to be done. I believe General Botha intended to concentrate the troops round Pretoria, and there offer some sort of resistance to the triumphant forces of the enemy, and we had all understood that the capital would be defended to the last; but this communication altered the position considerably. Shortly afterwards all the Boer officers met at Irene Estate, near Pretoria, in a council of war, and were there informed that the Government had already forsaken the town, leaving a few “feather-bed patriots” to formally surrender the town to the English.

I thought this decision of easy surrender ridiculous and inexplicable, and many officers joined me in loud condemnation of it. I do not remember exactly all that happened at the time, but I know a telegram arrived from the Commandant-General saying that a crowd had broken open the Commissariat Buildings in Pretoria and were looting them. An adjutant was sent into Pretoria to spread an alarm that the English were entering the town, and this had the effect of driving all the looters out of it. Some of my own men were engaged in these predatory operations, and I did not see them again until three days after.

The English approached Pretoria very cautiously, and directed some big naval guns on our forts built round the town, to which we replied for some time with our guns from the “randten,” south-west of the town; but our officers were unable to offer any organised resistance, and thus on the 5th of June, 1900, the capital of the South African Republic fell with little ado into the enemy’s hands. Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State, had months before suffered the same fate, and thousands of Free Staters had surrendered to the English as they marched from Bloemfontein to the Transvaal. Happily, however, in the Free State President Steyn and General De Wet were still wide awake and Lord Roberts very soon discovered that his long lines of communication were a source of great trouble and anxiety to him. The commandos, meanwhile, were reorganised; the buried Mausers and ammunition were once more resurrected, and soon it became clear that the Orange Free State was far from conquered.

The fall of Pretoria, indeed, was but a sham victory for the enemy. A number of officials of the Government remained behind there and surrendered, together with a number of burghers, amongst these faint-hearted brethren being even members of the Volksraad and men who had played a prominent part in the Republic’s history; while to the everlasting shame of them and their race, a number of other Boers entered at once into the English service and henceforth used their rifles to shoot at and maim their own fellow-countrymen.

CHAPTER XVI

BATTLE OF DONKERHOEK (“DIAMOND HILL”).

Our first and best positions were now obviously the kopjes which stretched from Donkerhoek past Waterval and Wonderboompoort. This chain of mountains runs for about 12 miles E. and N.E. of Pretoria, and our positions here would cut off all the roads of any importance to Pietersburg, Middelburg, as well as the Delagoa Bay railway. We therefore posted ourselves along this range, General De la Rey forming the right flank, some of our other fighting generals occupying the centre, whilst Commandant-General Botha himself took command of the left flank.

On the 11th of June, 1900, Lord Roberts approached with a force of 28,000 to 30,000 men and about 100 guns, in order, as the official despatches had it, “to clear the Boers from the neighbourhood of Pretoria.” Their right and left flanks were composed of cavalry, whilst the centre was formed of infantry regiments; their big guns were placed in good positions and their field pieces were evenly distributed amongst the different army divisions.

Towards sunset they began booming away at our whole 13 miles of defence. Our artillery answered their fire from all points with excellent results, and when night fell the enemy retired a little with considerable losses.

The battle was renewed again next day, the enemy attempting to turn our right with a strong flanking movement, but was completely repulsed. Meanwhile I at Donkerpoort proper had the privilege of being left unmolested for several hours. The object of this soon became apparent. A little cart drawn by two horses and bearing a white flag came down the road from Pretoria. From it descended two persons, Messrs. Koos Smit, our Railway Commissioner and Mr. J. F. de Beer, Chief Inspector of Offices, both high officials of the South African Republic. I called out to them from a distance.

“Halt, you cannot pass. What do you want?”

Smit said, “I want to see Botha and President Kruger. Dr. Scholtz is also with us. We are sent by Lord Roberts.”

I answered Mr. Smit that traitors were not admitted on our premises, and that he would have to stay where he was. Turning to some burghers who were standing near I gave instructions that the fellows were to be detained.

Mr. Smit now began to “sing small,” and turning deadly pale, asked in a tremulous voice if there were any chance of seeing Botha.

“Your request,” I replied, “will be forwarded.” Which was done.

An hour passed before General Botha sent word that he was coming. Meanwhile the battle continued raging fiercely, and a good many lyddite bombs were straying our way. The “white-flaggists” appeared to be very anxious to know if the General would be long in coming, and if their flag could not be hoisted in a more conspicuous place. The burghers guarding them pointed out, however, that the bombs came from their own British friends.

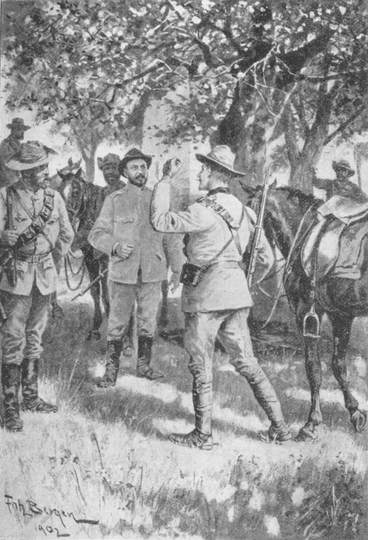

After a while General Botha rode up. He offered a far from cordial welcome to the deputation.

Dr. Scholtz produced a piece of paper and said Lord Roberts had sent him to enquire why Botha insisted on more unnecessary bloodshed, and why he did not come in to make peace, and that sort of thing.

Botha asked if Scholtz held an authoritative letter or document from the English general, to which the Doctor replied in the negative.

Smit now suggested that he should be allowed to see Mr. Kruger, but Botha declared, with considerable emphasis, “Look here, your conduct is nothing less than execrable, and I shall not allow you to see Mr. Kruger. You are a couple of contemptible scoundrels, and as for Dr. Scholtz, his certificate looks rather dubious. You will go back and give the following message to Lord Roberts:—

“That this is not the first time messages of this description are sent to me in an unofficial manner; that these overtures have also sometimes been made in an insulting form, but always equally unofficially. I have to express my surprise at such tactics on the part of a man in Lord Roberts’ position. His Lordship may think that our country is lost to us, but I shall do my duty towards it all the same. They can shoot me for it or imprison me, or banish me, but my principles and my character they cannot assail.”

One could plainly see that the conscience-stricken messengers winced under the reproach. Not another word was said, and the noble trio turned on their heels and took their white flag back to Pretoria.

Whether Botha was right in allowing these “hands-uppers” to return, is a question I do not care to discuss, but many burghers had their own opinion about it. Still, if they had been detained by us and shot for high treason, what would not have been said by those who did not hesitate to send our own unfaithful burghers to us to induce us to surrender.

I cannot say whether Lord Roberts was personally responsible for the sending of these messengers, but that such action was extremely improper no one can deny. It was a specially stupendous piece of impudence on the part of these men, J. S. Smit and J. F. de Beer, burghers both, and highly placed officials of the S. A. Republic. They had thrown down their arms and sworn allegiance to an enemy, thereby committing high treason in the fullest sense of the word. They now came through the fighting lines of their former comrades to ascertain from the commanders of the republican army why the whole nation did not follow their example, why they would not surrender their liberty and very existence as a people and commit the most despicable act known to mankind.

“Pretoria was in British hands!” As if, forsooth, the existence of our nationality began and ended in Pretoria! Pretoria was after all only a village where “patriots” of the Smit and de Beer stamp had for years been fattening on State funds, and, having filled their pockets by means of questionable practices, had helped to damage the reputation of a young and virile nation.

Not only had they enjoyed the spoils of high office in the State Service offices, to which a fabulous remuneration was attached, but they belonged to the Boer aristocracy, members of honourable families whose high birth and qualities had secured for them preference over thousands of other men and the unlimited confidence of the Head of State. Little wonder these gentlemen regarded the fall of Pretoria as the end of the war!

The battle continued the whole day; it was fiercest on our left flank, where General French and his cavalry charged the positions of the Ermelo and Bethel burghers again and again, each time to be repulsed with heavy losses. Once the lancers attacked so valiantly that a hand-to-hand fight ensued. The commandant of the Bethel burghers afterwards told me that during the charge his kaffir servant got among the lancers and called upon them to “Hands up!” The unsophisticated native had heard so much about “hands up,” and “hands-uppers,” that he thought the entire English language consisted of those two simple words, and when one lancer shouted to him “Hands up,” he echoed “Hands up.” The British cavalryman thrust his lance through the nigger’s arm, still shouting “Hands up,” the black man retreating, also vociferously shrieking “Hands up, boss; hands up!”

When his master asked him why he had shouted “Hands up” so persistently though he was running away, he answered: “Ah, boss, me hear every day people say, ‘Hands up;’ now me think this means kaffir ‘Soebat’ (to beg). I thought it mean, ‘Leave off, please,’ but the more I shouted ‘Hands up’ English boss prod me with his assegai all the same.”

On our right General De la Rey had an equally awkward position; the British here also made several determined attempts to turn his flank, but were repulsed each time. Once during an attack on our right, their convoy came so close to our position that our artillery and our Mausers were enabled to pour such a fire into them that the mules drawing the carts careered about the veldt at random, and the greatest confusion ensued. British mules were “pro-Boer” throughout the War. The ground, however, was not favourable for our operations, and we failed to avail ourselves of the general chaos. Towards the evening of the second day General Tobias Smuts made an unpardonable blunder in falling back with his commandos. There was no necessity for the retreat; but it served to show the British that there was a weak point in our armoury. Indeed, the following day the attack in force was made upon this point. The British had meantime continued pouring in reinforcements, men as well as guns.

About two o clock in the afternoon Smuts applied urgently for reinforcements, and I was ordered by the Commandant-General to go to his position. A ride of a mile and a half brought us near Smuts; our horses were put behind a “randje,” the enemy’s bullets and shells meantime flying over their heads without doing much harm. We then hurried up on foot to the fighting line, but before we could reach the position General Smuts and his burghers had left it. At first I was rather in the dark as to what it all meant until we discovered that the British had won Smuts’ position, and from it were firing upon us. We fell down flat behind the nearest “klips” and returned the fire, but were at a disadvantage, since the British were above us. I never heard where General Smuts and his burghers finally got to. On our left we had Commandant Kemp with the Krugersdorpers; on the right Field-Cornet Koen Brits. The British tried alternately to get through between one of my neighbours and myself, but we succeeded, notwithstanding their fierce onslaught, in turning them back each time. All we could do, however, was to hold our own till dark. Then orders were given to “inspan” all our carts and other conveyances as the commandos would all have to retire.

I do not know the extent of the British losses in that engagement. My friend Conan Doyle wisely says nothing about them, but we knew they had suffered very severely indeed. Our losses were not heavy; but we had to regret the death of brave Field-Cornet Roelf Jansen and some other plucky burghers. Dr. Doyle, referring to the engagement, says:

“‘The two days’ prolonged struggle (Diamond Hill) showed that there was still plenty of fight in the burghers. Lord Roberts had not routed them,” etc.

Thus ended the battle of Donkerhoek, and next day our commandos were falling back to the north.

CHAPTER XVII

I BECOME A GENERAL.

In our retreat northwards the English did not pursue us. They contented themselves by fortifying the position we had evacuated between Donkerhoek and Wonderboompoort. Meantime our commandos proceeded along the Delagoa Bay Railway until we reached Balmoral Station, while other little divisions of ours were at Rhenosterkop, north of Bronkhorst Spruit.

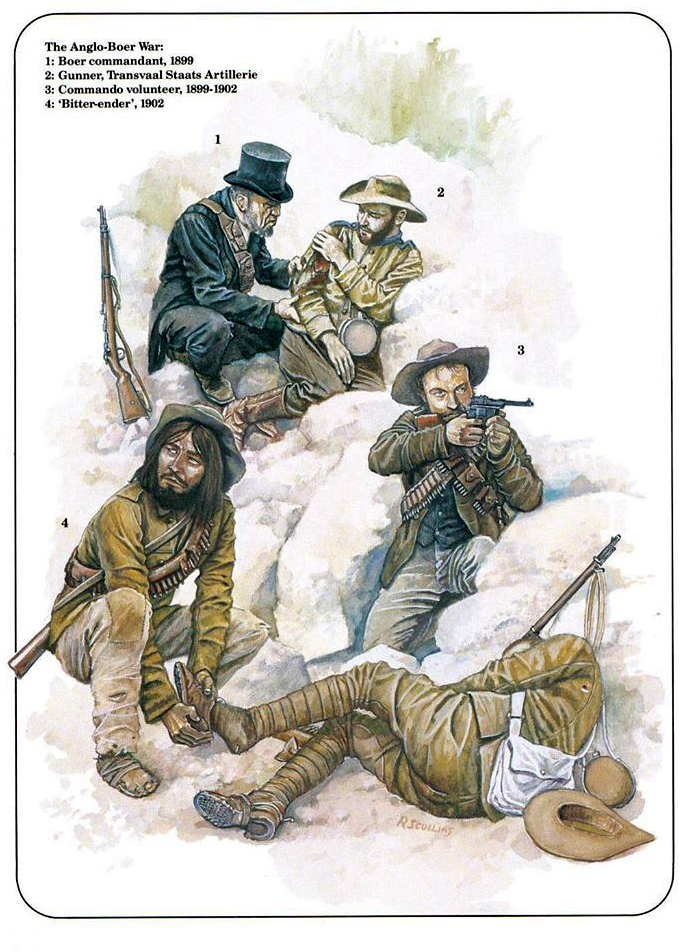

I may state that this general retreat knocked the spirit out of some of our weaker brethren. Hundreds of Boers rode into Pretoria with the white flag suspended from their Mauser barrels. In Pretoria there were many prominent burghers who had readily accepted the new conditions, and these were employed by the British to induce other Boers within reach, by manner of all sorts of specious promises, to lay down their arms. Many more western district Boers quietly returned to their homes. Luckily, the Boer loves his Mauser too well to part with it, except on compulsion, and although the majority of these western Boers handed in their weapons, some retained them.

They retained their weapons by burying them, pacifying the confiding British officer in charge of the district by handing in rusty and obsolete Martini-Henris or a venerable blunderbuss which nobody had used since ancestral Boer shot lions with it in the mediæval days of the first great trek. The buried Mausers came in very useful afterwards.

About this time General Buller entered the Republic from the Natal side, and marched with his force through the southern districts of Wakkerstroom, Standerton, and Ermelo. Hundreds of burghers remained on their farms and handed their weapons to the British. In some districts, for instance, at Standerton, the commandant and two out of his three field-cornets surrendered. Thus, not only were some commandos without officers, but others entirely disappeared from our army. Still, at the psychological moment a Joshua would appear, and save the situation, as, for instance, in the Standerton district, where Assistant-Field-Cornet Brits led a forlorn hope and saved a whole commando from extinction. The greatest mischief was done by many of our landdrosts, who, after having surrendered, sent out communications to officers and burghers exhorting them to come in.

The majority of our Boer officers, however, remained faithful to their vow, though since the country was partly occupied by the British it was difficult to get in touch with the Commandant-General or the Government, and the general demoralisation prevented many officers from asserting their authority.

Generals Sarel Oosthuizen and H. L. Lemmer, both now deceased, were sent to the north of Pretoria, to collect the burghers from the western districts, and to generally rehabilitate their commandos. They were followed by Assistant-Commandant General J. H. De la Rey and State Attorney Smuts (our legal adviser). It was at this point, indeed, that the supreme command of the western districts was assumed by General De la Rey, who, on his way to the north, attacked and defeated an English garrison at Selatsnek.

The “reorganisation” of our depleted commandos proceeded very well; about 95 per cent. of the fighting Boers rejoined, and speedily the commandos in the western districts had grown to about 7,000 men.

But just a few weeks after his arrival in the West Krugersdorp district, poor, plucky Sarel Oosthuizen was severely wounded in the battle of Dwarsvlei, and died of his wounds some time after.

General H. Lemmer, a promising soldier, whom we could ill spare, was killed soon after while storming Lichtenburg under General De la Rey, an engagement in which we did not succeed. We had much trouble in replacing these two brave generals, whose names will live for all time in the history of the Boer Republics.

It is hardly necessary to dwell on the splendid work done by Assistant-Commandant-General De la Rey in the western districts. Commandant-General Botha was also hard worked at this stage, and was severely taxed reorganising his commandos and filling up the lamentable vacancies caused by the deaths of Lemmer and Oosthuizen.

I have already pointed out that General De la Rey had taken with him the remainder of the burghers from the western districts. The following commandos were now left to us:—Krugersdorp and Germiston, respectively, under the then Commandants J. Kemp and C. Gravett, and the Johannesburg police, with some smaller commandos under the four fighting generals, Douthwaith, Snyman (of Mafeking fame), Liebenberg, and Du Toit. The last four generals were “sent home” and their burghers with those of Krugersdorp, Germiston, Johannesburg, Boksburg and the Mounted Police, were placed under my command, while I myself was promoted to the rank of General. I had now under me 1,200 men, all told—a very fair force.

I can hardly describe my feelings on hearing of my promotion to such a responsible position. For the first time during the War I felt a sort of trepidation. I had all sorts of misgivings; how should I be able to properly guard the interests of such a great commando? Had I a right to do so? Would the burghers be satisfied? It was all very well to say that they would have to be satisfied, but if they had shown signs of dissatisfaction I should have felt bound to resign. I am not in the habit of blinking at facts; they are stern things. What was to become of me if I had to tender my resignation? I was eager and rash, like most young officers, for although the prospects of our cause were not brilliant and our army had suffered some serious reverses, I still had implicit faith in the future, and above all, in the justice of the cause for which we were fighting. And I knew, moreover, that the burghers we now had left with us were determined and firm.

There was only one way open to me: to take the bull by the horns. I thought it my duty to go the round of all the commandos, call the burghers together, tell them I had been appointed, ask them their opinion on the appointment, and give them some particulars of the new organisation.

I went to the Krugersdorp Commando first. All went well, and the burghers comprising the force received me very cordially. There was a lot of questioning and explanations; one of the commandants was so moved by my address that he requested those who were present to conclude the meeting by singing Psalm 134, verse 3, after which he exhorted his fellow burghers in an impassioned speech to be obedient and determined.

The worst of it was that he asked me to wind up by offering a prayer. I felt as if I would gladly have welcomed the earth opening beneath me. I had never been in such a predicament before. To refuse, to have pleaded exoneration from this solemn duty, would have been fatal, for a Boer general is expected, amongst other things, to conduct all proceedings of a religious character. And not only Boer generals are required to do this thing, but all subordinate officers, and an officer who cannot offer a suitable prayer generally receives a hint that he is not worthy of his position. In these matters the burghers are backed up by the parsons.

There was, therefore, no help for it; I felt like a stranger in Jerusalem, and resolved to mumble a bit of a prayer as well as I could. I need not say it was short, but I doubt very much whether it was appropriate, for all sorts of thoughts passed through my head, and I felt as if all the bees in this world were buzzing about my ears. Of course I had to shut my eyes; I knew that. But I had, moreover, to screw them up, for I knew that everybody was watching me. I closed my eyes very tightly, and presently there came a welcome “Amen.”

My old commando was now obliged to find a new commandant and I had to take leave of them in that capacity. I was pleased to find the officers and men were sorry to lose me as their commandant, but they said they were proud of the distinction that had been conferred upon me. Commandant F. Pienaar, who took my place, had soon to resign on account of some rather serious irregularities. My younger brother, W. J. Viljoen, who, at the time of writing, is, I believe, still in this position, replaced him.

At the end of June my commandos marched from Balmoral to near Donkerhoek in order to get in touch with the British. Only a few outpost skirmishes took place.

My burghers captured half a score of Australians near Van der Merwe Station, and three days afterwards three Johannesburgers were surprised near Pienaarspoort. As far as our information went the Donkerhoek Kopjes were in possession of General Pole-Carew, and on our left General Hutton, with a strong mounted force, was operating near Zwavelpoort and Tigerspoort. We had some sharp fighting with this force for a couple of days, and had to call in reinforcements from the Middelburg and Boksburg commandos.

The fighting line by this time had widely extended and was at least sixty miles in length; on my right I had General D. Erasmus with the Pretoria commando, and farther still to the right, nearer the Pietersburg railway, the Waterberg and Zoutpansberg commandos were positioned. General Pole-Carew tried to rush us several times with his cavalry, but had to retire each time. Commandant-General Botha finally directed us to attack General Hutton’s position, and I realised what this involved. It would be the first fight I had to direct as a fighting general. Much would depend on the issue, and I fully understood that my influence with, and my prestige among, the burghers in the future was absolutely at stake.

General Hutton’s main force was encamped in a “donk” at the very top of the randt, almost equidistant from Tigerspoort, Zwavelpoort and Bapsfontein. Encircling his laager was another chain of “randten” entirely occupied and fortified, and we soon realised what a large and entrenched stretch of ground it was. The Commandant-General, accompanied by the French, Dutch, American and Russian attachés, would follow the attack from a high point and keep in touch with me by means of a heliograph, thus enabling Botha to keep well posted about the course of the battle, and to send instructions if required.

During the night of the 13th of July we marched in the following order: On the right were the Johannesburg and Germiston commandos; in the centre the Krugersdorp and the Johannesburg Police; and on the left the Boksburg and Middelburg commandos. At daybreak I ordered a general storming of the enemy’s entrenchments. I placed a Krupp gun and a Creusot on the left flank, another Krupp and some pom-poms to the right, while I had an English 15-pounder (an Armstrong) mounted in the centre. Several positions were taken by storm with little or no fighting. It was my right flank which met with the only stubborn resistance from a strongly fortified point occupied by a company of Australians.

Soon after this position was in our possession, and we had taken 32 prisoners, with a captain and a lieutenant. When Commandant Gravett had taken the first trenches we were stubbornly opposed in a position defended by the Irish Fusiliers, who were fighting with great determination. Our burghers charged right into the trenches; and a hand-to-hand combat ensued. The butt-ends of the guns were freely used, and lumps of rock were thrown about. We made a few prisoners and took a pom-pom, which, to my deep regret, on reinforcements with guns coming up to the enemy, we had to abandon, with a loss of five men. Meanwhile, the Krugersdorpers and Johannesburg Police had succeeded in occupying other positions and making several prisoners, while half a dozen dead and wounded were left on the field.

The ground was so exposed that my left wing could not storm the enemy’s main force, especially as his outposts had noticed our march before sunrise and had brought up a battery of guns, and in this flat field a charge would have cost too many lives.

We landed several shells into the enemy’s laager, and if we had been able to get nearer he would certainly have been compelled to run.

When darkness supervened we retired to our base with a loss of two killed and seven wounded; whereas 45 prisoners and 20 horses with saddles and accoutrements were evidence that we had inflicted a severe loss upon the enemy. So far as I know, the Commandant-General was satisfied with my work. On the day after the fight I met an attaché. He spoke in French, of which language I know nothing. My Gallic friend then tried to get on in English, and congratulated me in the following terms with the result of the fight: “I congratuly very much you, le Général; we think you good man of war.” It was the first time I had bulked in anyone’s opinion as largely as a battleship; but I suppose his intentions were good enough.

A few days afterwards Lord Roberts sent a hundred women and children down the line to Van der Merwe Station, despite Botha’s vehement protests. It fell to my lot to receive these unfortunates, and to send them on by rail to Barberton, where they could find a home. I shall not go into a question which is still sub judice; nor is it my present purpose to discuss the fairness and unfairness of the war methods employed against us. I leave that to abler men. I shall only add that these waifs were in a pitiful position, as they had been driven from their homes and stripped of pretty nearly everything they possessed.

Towards the end of July Carrington marched his force to Rustenburg, and thence past Wonderboompoort, while another force proceeded from Olifantsfontein in the direction of Witbank Station. We were, therefore, threatened on both sides and obliged to fall back on Machadodorp.

CHAPTER XVIII

OUR CAMP BURNED OUT.

The beginning of August saw my commandos falling back on Machadodorp. Those of Erasmus and Grobler remained where they were for the time being, until the latter was discharged for some reason or other and replaced by Attorney Beyers. General Erasmus suffered rather worse, for he was deprived of his rank as a general and reduced to the level of a commandant on account of want of activity.

Our retreat to Machadodorp was very much like previous experiences of the kind; we were continually expecting to be cut off from the railway by flanking movements and this we had to prevent because we had placed one of our big guns on the rails in an armour-clad railway carriage. The enemy took care to keep out of rifle range, and the big gun was an element of strength we could ill afford to lose. Besides, our Government were now moving about on the railway line near Machadodorp, and we had to check the enemy at all hazards from stealing a march on us. Both at Witbank Station and near Middelburg and Pan Stations we had skirmishes, but not important enough to describe in detail.

After several unsuccessful attempts, the Boer Artillery at last managed to fire the big gun without a platform. It was tedious work, however, as “Long Tom” was exceedingly heavy, and it usually took twenty men to serve it. The mouth was raised from the “kastion” by means of a pulley, and the former taken away; then and not till then could the gunner properly get the range. The carriage vacuum sucking apparatus had to be well fixed in hard ground to prevent recoil.

The enemy repeatedly sent a mounted squad to try and take this gun, and then there was hard fighting.

One day while we were manœuvring with the “Long Tom,” the veldt burst into flames, and the wind swept them along in our direction like lightning. Near the gun were some loads of shells and gunpowder, and we had to set all hands at work to save them. While we were doing this the enemy fired two pom-poms at us from about 3,000 yards, vastly to our inconvenience.

As my commando formed a sort of centre for the remainder, Commandant-General Botha was, as a rule, in our immediate neighbourhood, which made my task much easier, our generalissimo taking the command in person on several occasions, if required, and assisting in every possible way.

The enemy pursued us right up to Wonderfontein Station (the first station south-west of Belfast), about 15 miles from Dalmanutha or Bergendal, and waited there for Buller’s army to arrive from the Natal frontier.

We occupied the “randten” between Belfast and Machadodorp, and waited events. While we were resting there Lord Roberts sent us 250 families from Pretoria and Johannesburg in open trucks, notwithstanding the bitterly cold weather and the continual gusts of wind and snow. One can picture to oneself the deplorable condition we found these women and children in.

But, with all this misery, we still found them full of enthusiasm, especially when the trucks in which they had to be sent on down the line were covered with Transvaal and Free State flags. They sang our National Anthem as if they had not a care in the world.

Many burghers found their families amongst these exiles, and some heartrending scenes were witnessed. Luckily the railway to Barberton was still in our possession, and at Belfast the families were taken over from the British authorities, to be sent to Barberton direct. While this was being done near Belfast under my direction, the unpleasant news came that our camp was entirely destroyed by a grass fire.

The Commandant-General and myself had set up our camp near Dalmanutha Station. It consisted of twelve tents and six carts. This was Botha’s headquarters, as well as of his staff and mine. When we came to the spot that night we found everything burned save the iron tyres of the waggon wheels, so that the clothes we had on were all we had left us. All my notes had perished, as well as other documents of value. I was thus deprived of the few indispensable things which had remained to me, for at Elandslaagte my “kit” had also fallen into the hands of the British. The grass had been set on fire by a kaffir to the windward of the camp. The wind had turned everything into a sea of fire in less than no time, and the attempts at stamping out the flames had been of no avail. One man gave us a cart, another a tent; and the harbour at Delagoa Bay being still open (although the Portuguese had become far from friendly towards us after the recent British victories) we managed to get the more urgent things we wanted. Within a few days we had established a sort of small camp near to headquarters.

We had plenty to do at this time—building fortresses and digging trenches for the guns. This of course ought to have been done when we were still at Donkerhoek by officers the Commandant-General had sent to Machadodorp for the purpose. We had made forts for our “Long Toms,” which were so well hidden from view behind a rand that the enemy had not discovered them, although a tunnel would have been necessary in order to enable us to use them in shelling the enemy. We were therefore obliged to set to work again, and the old trenches were abandoned. The holes may surprise our posterity, by the way, as a display of the splendid architectural abilities of their ancestors.

CHAPTER XIX

BATTLE OF BERGENDAL (MACHADODORP).

Let us pass on to the 21st of August, 1900. Buller’s army had by this time effected a junction with that of Lord Roberts’ between Wonderfontein and Komati River. The commandos under Generals Piet Viljoen and Joachim Fourie had now joined us, and taken up a position on our left, from Rooikraal to Komati Bridge. The enemy’s numbers were estimated at 60,000, with about 130 guns, including twelve 4.7 naval guns, in addition to the necessary Maxims.

We had about 4,000 men at the most with six Maxims and about thirteen guns of various sizes. Our extreme left was first attacked by the enemy while they took possession of Belfast and Monument Hill, a little eastward, thereby threatening the whole of our fighting lines. My commandos were stationed to the right and left of the railway and partly round Monument Hill. Fighting had been going on at intervals all day long, between my burghers and the enemy’s outposts. The fighting on our left wing lasted till late in the afternoon, when the enemy was repulsed with heavy losses; while a company of infantry which had pushed on too far during the fighting, through some misunderstanding or something of that sort, were cut off and captured by the Bethel burghers.

The attack was renewed the next morning, several positions being assailed in turn, while an uninterrupted gunfire was kept up. General Duller was commanding the enemy’s right flank and General French was in charge of the left. We were able to resist all attacks and the battle went on for six days without a decisive result. The enemy had tried to break through nearly every weak point in our fighting line and found out that the key to all our positions existed in a prominent “randje” to the right of the railway. This point was being defended by our brave Johannesburg police, while on the right were the Krugersdorpers and Johannesburgers and to the left the burghers from Germiston. Thus we had another “Spion Kop” fight for six long days. The Boers held their ground with determination, and many charges were repulsed by the burghers with great bravery. But the English were not to be discouraged by the loss of many valiant soldiers and any failure to dislodge the Boers from the “klip-kopjes.” They were admirably resolute; but then they were backed up by a superior force of soldiers and artillery.

On the morning of the 27th of August the enemy were obviously bent on concentrating their main force on this “randje.” There were naval guns shelling it from different directions, while batteries of field-pieces pounded away incessantly. The “randje” was enveloped by a cloud of smoke and dust. The British Infantry charged under cover of the guns, but the Police and burghers made a brave resistance. The booming of cannon went on without intermission, and the storming was repeated by regiment upon regiment. Our gallant Lieutenant Pohlman was killed in this action, and Commandant Philip Oosthuizen was wounded while fighting manfully against overwhelming odds at the head of his burghers. An hour before sunset the position fell into the hands of the enemy. Our loss was heavy—two officers, 18 men killed or wounded, and 20 missing.

Thus ended one of the fiercest fights of the war. With the exception of the battle of Vaalkrantz (on the Tugela) our commandos had been exposed to the heaviest and most persistent bombardment they had yet experienced. It was by directing an uninterrupted rifle fire from all sides on the lost “randje” that we kept the enemy employed and prevented them from pushing on any farther that evening.

At last came the final order for all to retire via Machadodorp.

CHAPTER XX

TWO THOUSAND BRITISH PRISONERS RELEASED.

After the battle of Bergendal there was another retreat. Our Government, which had fled from Machadodorp to Waterval Station, had now reached Nelspruit, three stations further down the line, still “attended,” shall I say, by a group of Boer officials and members of the Volksraad, who preferred the shelter of Mr. Kruger’s fugitive skirts to any active fighting. There were also hovering about this party half a dozen Hebraic persons of extremely questionable character, one of whom had secured a contract for smuggling in clothes from Delagoa Bay; and another one to supply coffee and sugar to the commandos. As a rule, some official or other made a nice little commission out of these transactions, and many burghers and officers expressed their displeasure and disgust at these matters; but so it was, and so it remained. That same night we marched from Machadodorp to Helvetia, where we halted while a commando was appointed to guard the railway at Waterval Boven.

The next morning a big cloud of dust arose. “De Engelse kom” (the English are coming) was the cry. And come they did, in overwhelming numbers. We fired our cannon at their advance guard, which had already passed Machadodorp: but the British main force stayed there for the day, and a little outpost skirmishing of no consequence occurred.

A portion of the British forces appeared to go from Belfast via Dullstroom to Lydenburg, these operations being only feebly resisted. Our commandos were now parcelled out by the Commandant-General, who followed a path over the Crocodile River bridge with his own section, which was pursued by a strong force of Buller’s.

I was ordered to go down the mountain in charge of a number of Helvetia burghers to try and reach the railway, which I was to defend at all hazards. General Smuts, with the remnant of our men went further south towards the road leading to Barberton. Early the next morning we were attacked and again obliged to fall back. That night we stayed at Nooitgedacht.

The Boer position at and near Nooitgedacht was unique. Here was a great camp in which 2,000 English prisoners-of-war were confined, but in the confusion the majority of their Boer guards had fled to Nelspruit. I found only 15 burghers armed with Martini-Henry rifles left to look after 2,000 prisoners. Save for “Tommy” being such a helpless individual when he has nobody to give him orders and to think for him, these 2,000 men might have become a great source of danger to us had they had the sense to disarm their fifteen custodians (and what was there to prevent them doing so?) and to destroy the railway, they would have been able not only to have deprived my commando of provisions and ammunition, but also to have captured a “Long Tom.” There was, moreover, a large quantity of victuals, rifles, and ammunition lying about the station, of which nobody appeared to take any notice. Of the crowd of officials who stuck so very faithfully to the fugitive Government there was not one who took the trouble to look after these stores and munitions.

On arrival I telegraphed to the Government to enquire what was to be done with the British prisoners-of-war. The answer was: “You had better let them be where they are until the enemy force you to evacuate, when you will leave them plenty of food.”

This meant that there would be more D.S.O’s or V.C’s handed out, for the first “Tommies” to arrive at the prisoners’ camp would be hailed as deliverers, and half of them would be certain of distinctions.

I was also extremely dissatisfied with the way the prisoners had been lodged, and so would any officer in our fighting line have been had he seen their condition and accommodation. But those who have never been in a fight and who had only performed the “heroic” duty of guarding prisoners-of-war, did not know what humanity meant to an enemy who had fallen into their hands.

So what was I to do?

To disobey the Government’s orders was impossible. I accordingly resolved to notify the prisoners that, “for military reasons,” it would be impossible to keep them in confinement any longer.

The next morning I mustered them outside the camp, and they were told that they had ceased to be prisoners-of-war, at which they seemed to be very much amazed. I was obliged to go and speak formally to some of them; they could scarcely credit that they were free men and could go back to their own people. It was really pleasant to hear them cheer, and to see how pleased they were. A great crowd of them positively mobbed me to shake hands with them, crying, “Thank you, sir; God bless you, sir.” One of their senior officers was ordered to take charge of them, while a white-flag message was sent to General Pole-Carew to send for these fine fellows restored to freedom, and to despatch an ambulance for the sick and wounded. My messenger, however, did not succeed in delivering the letter, as the scouts of the British advance-guard were exceedingly drunk, and shot at him; so that the prisoners-of-war had to go out and introduce themselves. I believe they were compelled to overpower their own scouts.

Ten days afterwards an English doctor and a lieutenant of the 17th Lancers came to us, bringing a mule laden with medical appliances and food. The English medico, Dr. Ailward, succeeded, moreover, in getting through our lines without my express permission.

Next morning I accompanied an ambulance train to transport the wounded British to the charge of the British agent at Delagoa Bay. Outside Nooitgedacht I found four military doctors with a field ambulance.

“Does this officer belong to the Red Cross?” I asked.

“No,” was the answer, “he is only with us quite unofficially as a sympathetic friend.”

“I regret,” said I, “that I cannot allow this thing; you have come through our lines without my permission; this officer no doubt is a spy.”

I wired at once for instructions, which, when received read: “That as a protest against the action of the English officers who stopped three of our ambulances, and since this officer has passed through our lines without permission, you are to stop the ambulance and dispatch the doctors and their staff, as well as the wounded to Lourenco Marques.”

The doctors were very angry and protested vehemently against the order, which, however, was irrevocable. And thus the whole party, including the Lancers’ doctor, were sent to Lourenco Marques that very day. The nearest English General was informed of the whole incident, and he sent a very unpleasant message the next day, of which I remember the following phrases:—

“The action which you have taken in this matter is contrary to the rules of civilised warfare, and will alter entirely the conditions upon which the War was carried on up to the present,” etc.

After I had sent my first note we found, on inspection, some Lee-Metford cartridges and an unexploded bomb in the ambulance vans. This fact alone would have justified the retention of the ambulance.

This was intimated again in our reply to General Pole-Carew, and I wrote, inter alia: “Re the threat contained in your letter of the … I may say I am sorry to find such a remark coming from your side, and I can assure you that whatever may happen my Government, commandants, and burghers are firmly resolved to continue the War on our side in the same civilised and humane manner as it has hitherto been conducted.”

This was the end of our correspondence in regard to this subject, and nothing further happened, save that the English very shortly afterwards recovered five out of the eight ambulances we had retained.