Editor’s note: The following is extracted from Enemy In Sight!, by Stanley Rogers (published 1943).

At the beginning of the war Great Britain possessed six aircraft carriers — Ark Royal, Courageous, Glorious, Furious, Eagle, and Hermes—with another, Argus, used as a training ship. There were six others besides, building, their names given in Jane’s Fighting Ships as Illustrious, Victorious, Formidable, Indomitable, Implacable, and Indefatigable, all big ships. The first four were laid down in 1937 and were due for completion in 1940–41. Since Illustrious and Victorious and Formidable figured in the news before June 1941, it was then known that the first three of these four were completed and on active service. Courageous, sister-ship of Glorious, was the first major naval casualty of the war. She was torpedoed in September 1939 by an enemy submarine. Glorious was sunk by shell-fire from the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau off Norway in June 1940. They were both designed as cruisers during the World War of 1914–18 for operations in the Baltic — hence their shallow draught. After the war the cruisers were converted to aircraft carriers and were ready for their new role in 1930.

The first aircraft carriers, commissioned during the World War of 1914–18, were called ‘the hush-hush ships’ as their building was kept secret. They were converted from cruisers and were the original Furious and Argus. The first carrier to be built expressly for that purpose was HMS Hermes. She was fitted to carry twenty airplanes, and was the first carrier to have a flight deck extending the full length of the ship without a break. Her superstructure — funnel, bridge, and signaling mast — was built on the starboard side, a practice that was adopted in all subsequent vessels of this type. In 1913 there was laid down at Armstrong Whitworth’s yard at Tyneside a battleship for the Chilean government to be named Almirante Cochrane, but all work on the ship ceased in August 1914. In 1917 the British government purchased her from Chile for £1,334,358, and put the half-built ship in hand at Portsmouth Dockyard for conversion to an aircraft carrier. As HMS Eagle (22,600 tons displacement, and the largest vessel of its kind in the world) she was finally completed in 1924. Two more hush-hush cruisers, HMS Courageous and HMS Glorious, as we have said, were converted into aircraft carriers and completed in 1928 and 1930.

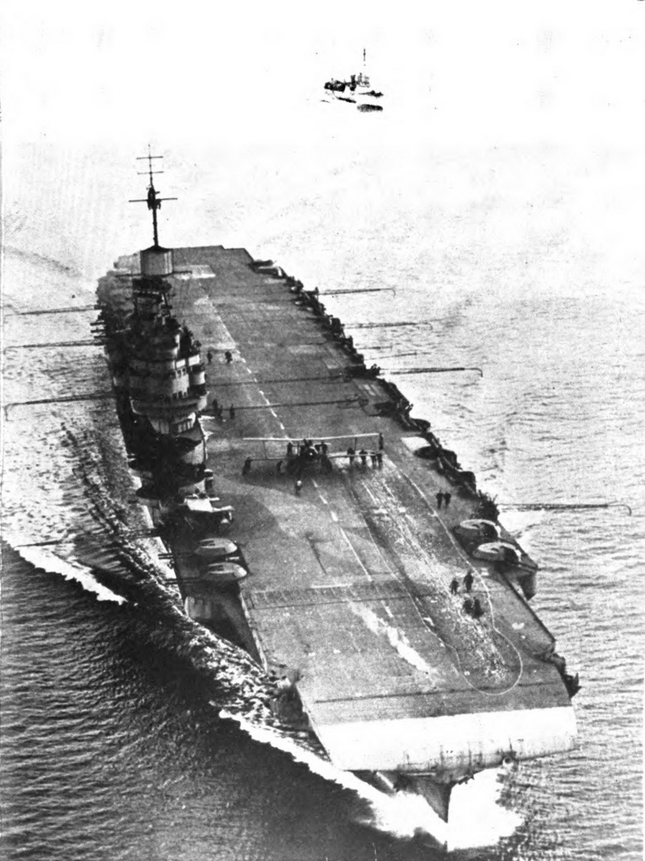

Illustrious was laid down in the yards of Vickers Armstrong at Barrow-in-Furness on April 4, 1937, as one of the big carriers budgeted for in the rearmament programme following the long sleep of the British government after the Treaty of Versailles. With a displacement of 23,000 tons, she was bigger than Ark Royal, which was completed in November 1938. Her length was 753 feet, and the width of the flight-deck 95 3/4 feet. Like her sister ships, her full complement was 1600 men. Space for seventy airplanes was provided for, though sixty was accepted as a more practical figure for operational purposes. Her defensive armament consisted of sixteen 4.5 dual purpose guns mounted on sponsons along either side, flush with the flight deck. Besides these guns she carried the usual batteries of multiple pom-poms. Japan and the United States equipped their carriers with 8-inch guns, but the Admiralty, moved by the principle that aircraft carriers should not be risked in offensive operations, had adhered to the policy of defensive armament only.

Put into commission in the autumn of 1940, Illustrious was sent almost before her paint was dry to assist the overworked Mediterranean Fleet. Her commander, Captain D. W. Boyd, C.B.E., D.S.C., was a naval officer of long experience, and before this cruise was over the wisdom of the Admiralty’s choice was to be amply justified. Under sealed orders the biggest and newest of the Royal Navy’s aircraft carriers left Britain, and after an uneventful voyage through the ‘Bay’ passed the Straits of Gibraltar and entered the Mediterranean, where her captain had instructions to keep his planes busy watching the skies and the seas for Axis aircraft and surface craft. Up to then the Navy had been unable to spare a modern carrier for these waters, and the arrival of Illustrious was a great relief to every British naval officer and rating in the Mediterranean. Axis planes had done much mischief among convoys, and at any moment the home-keeping Italian Navy might come out of their bases and challenge the Royal Navy. The presence of Illustrious soon began to be felt by the enemy, for her planes swept the skies and gave the Navy the freedom of movement it so desperately needed to protect convoys and the Suez Canal. But this was not spectacular work, and very few people in Britain were even aware that such a ship as Illustrious existed. Then came the famous raid on Taranto harbor, and her name appeared for the first time in the news.

On the night of November 11–12, 1940, the great naval base inside the heel of Italy was raided by torpedo-carrying aircraft from HMS Illustrious and HMS Eagle, an old ship. It was no coincidence that this most determined attack was carried out on the anniversary of the Armistice after the World War of 1914–18. In the harbor lay the main Italian battle fleet, comprising the two new battleships Littorio and Vittorio Veneto and four others of the Cavour class as well as a number of cruisers and auxiliary craft. The attack was so carefully planned that the enemy was caught off his guard with such successful results for the Royal Navy that the balance of naval power was decisively altered in favor of Britain. In one night torpedo carrying Swordfish and Skua dive-bombers flying from Illustrious and Eagle at sea forty miles away wrought fearful destruction. The Swordfishes, coming in low over the water, dropped their torpedoes at point-blank range, leaving two battleships (one of 35,000 tons and the other of 23,000 tons) severely handled and half submerged in the harbor. Another battleship was badly damaged, and two cruisers had taken a heavy list to starboard. A daylight reconnaissance carried out the next day showed two of the Cavour class battleships to be aground, another partly submerged and abandoned, and a big 35,000-ton Littorio battleship with her stern underwater and surrounded by salvage craft. Several smaller vessels could be detected lying underwater in the inner harbor. This single raid had put out of action half the Italian battle fleet at the cost of two British planes. For the first time in war the aircraft carrier had scored a major victory, and in doing so she had thoroughly justified herself.

So incensed were the German and Italian High Commands at this audacious raid that they issued orders that at any cost the aircraft carrier Illustrious must be destroyed. All other operations in the Mediterranean were to take second place in importance to this urgent and supreme necessity. For weeks German and Italian bomber planes searched for her, but it was not until January 10 that they caught her, south of Malta, and with all the pent-up fury of thwarted hunters did their best to sink the giant ship. Illustrious was part of a squadron covering the passage of a convoy of ships taking supplies to Greece. The attack took place in the Sicilian Channel, the bottle neck of the Mediterranean which lies between the island of Sicily and Cape Bon, on the African coast. Almost midway in the channel lies the small Italian island-fortress of Pantelleria, which had a small aerodrome and a base for U-boats. As the narrowest part of the Mediterranean it was the danger spot for convoys—a fact that the enemy did not fail to take advantage of.

The first news of the attack published in the more moderate British newspapers was a masterpiece of understatement. After announcing that a sea and air action had taken place in the Mediterranean, in which three British ships had been hit and damaged and twelve Axis planes had been brought down, and that the destroyer Gallant had been damaged but reached port, the London Times stated that the aircraft carrier had been hit and had received some damage. War-time censorship of necessity waters down spectacular news, and for weeks, if not months, the story of the hell Illustrious had been through was suppressed. But, piecing together the events of that dramatic day from official communiqués and from eye witness accounts, we can get a whole picture.

The convoy, escorted by warships, was half-way through the Sicilian Channel and heading eastward at dawn on January 10. Just as the first streaks of dawn were rising from the eastern horizon a star shell was seen curving up from a British destroyer which had sighted the dark shapes of two Italian destroyers several miles away. At the signal British cruisers and destroyers raced to overtake the enemy, firing salvos as they took up the chase. One of the enemy destroyers managed to escape to the north, but the other, a Spica class destroyer, crippled by the British guns, slowed down and was sent to the bottom by a British destroyer, which went in and finished her with a torpedo.

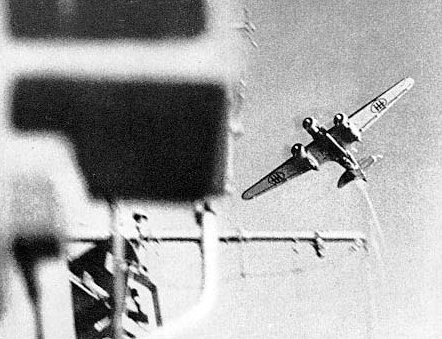

As the escorting destroyers were tearing about, the drone of enemy aircraft was heard, and high up in the winter sky unidentified enemy planes were seen approaching, Illustrious at once sent off a squadron of her own planes, which roared up and chased the enemy away. These planes turned out to be Italian machines from Sicily, and though they were driven off, it was not before they had radioed a report of the presence of the British convoy and its size. One hour later — at 12.15 P.M. – two Italian torpedo-bombers, coming out of the sun, dived at Illustrious and dropped their tin fish. The vicious anti-aircraft fire from Illustrious and other ships undoubtedly upset their aim, for both torpedoes missed, but one passed too close astern for comfort. The carrier had eighteen of her own planes in the air during this attack, but no others were able to leave her spacious flight deck that day, for a quarter of an hour later a large force (as many as forty-five were counted) of German and Italian dive bombers appeared and dived straight at Illustrious, leaving no doubt at all that their instructions were to concentrate on this ship and destroy her at whatever the cost.

With reckless courage they came straight in, ignoring the almost solid wall of anti-aircraft shells that screamed up to stop them. With daring and skill the attack was pressed home, though planes fell out of the sky like winged ducks. Hell broke loose over and around the victim of their fury. The sea was churned up into spouting columns of water and plumed spray as the Stukas rained down a torrent of bursting steel. Goggled pilots frowning down at the oblong shape of the carrier a thousand feet below, fatalistically ignoring the vicious, spitting anti-aircraft guns, were bent almost impersonally on one relentless purpose — to destroy that hated symbol of Britain’s sea-power.

Hammering her implacably with showers of heavy high explosives, indifferent to the wholesale slaughter of those British sailors, human beings like themselves, but turned enemies by the accident of war, the Nazi pilots pressed their attack with all the concentrated fury of their fanatical desire to destroy without mercy. They had been told that it was the planes of this ship that had caused the greatest destruction among the ships of their Italian ally at Taranto.

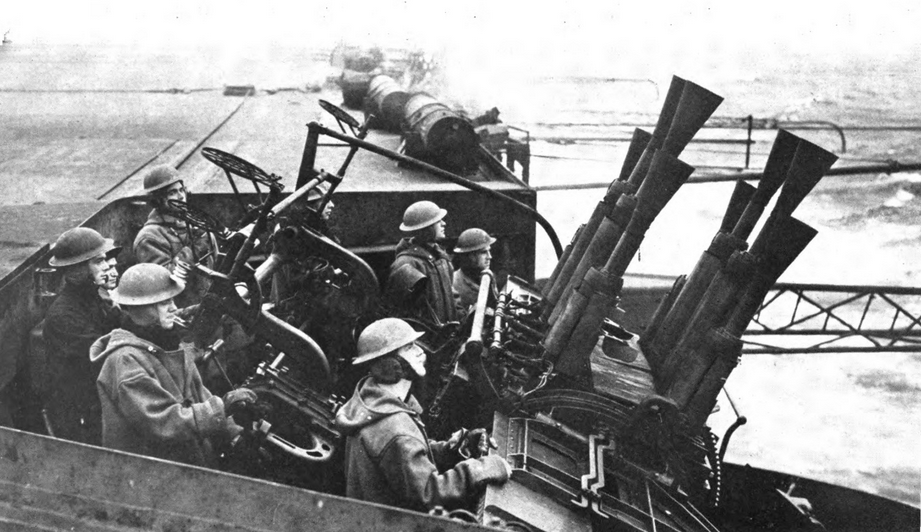

Other naval ships in the vicinity did what they could to protect the giant carrier, filling the blue Mediterranean sky with the dirty smudges of bursting A.A. shells. Watchers from the ships could see that Illustrious was taking terrible punishment and had received at least one direct hit on the flight deck by a bomb of heavy caliber. Some times the carrier was entirely blotted out by the columns of water and smoke from bursting bombs, but she was still fighting back gamely, her gunners remaining at their posts on the exposed gun platforms in spite of appalling casualties. Wave after wave of Stukas roared down on her, screaming like shells as they dived with their throttles wide open.

With jagged fragments of steel flying in every direction it was impossible for any of her crew to appear on deck. Still the gunners remained at their stations, though the crew of a multiple pom-pom were all killed when the gun received a direct hit from a bomb. A 1250-pound bomb, hitting the rear elevator hatch which was open and bringing up more planes, destroyed the planes and killed the crews.

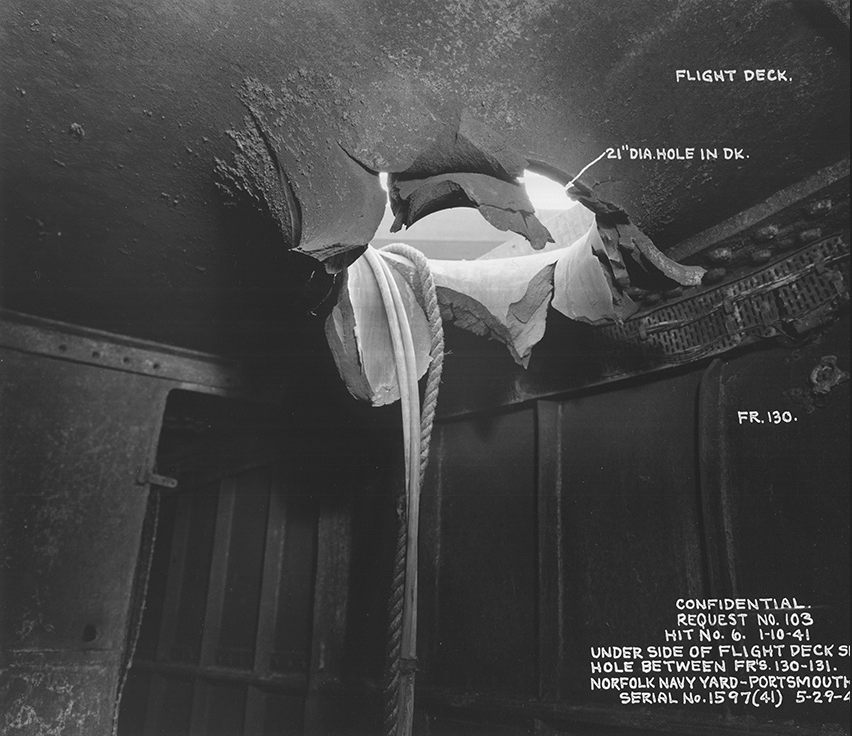

At 1:30 P.M. a second wave of thirty-five Stukas approached, flying high, and when over the carrier broke into flights of three, and with throttles wide open dived to attack. Good bomb sights or good luck got them another direct hit on the unfortunate ship. This time the after-part of the flight deck was hit, and a huge, ragged hole torn in the steel. The bomb burst in the hangar deck below, utterly destroying the closely packed planes and blowing the wreckage into a chaotic mess at one end of the vast hangar. Thousands of gallons of escaping gasoline from burst tanks caught fire, and the burning spirit running down openings in the deck started numerous fires below. Bomb splinters which penetrated steam pipes filled the engine room with scalding steam.

Although half the men there were wounded, superhuman efforts were made to quench the fires and suppress the escaping steam. These men, imprisoned in a flaming inferno, fought with selfless valor to save their ship — and succeeded. Dragging the dead aside, they rigged and manned the firefighting apparatus, and, while the great ship rocked with the titanic concussion of explosions, they remained at their posts in the face of what appeared certain death. As the electric generating system was disabled and cables cut, all lights went out, and the heroic firefighters worked by the light of the flames. To add to the hell between decks, bombs bursting below the water line buckled plating and let in torrents of seawater which flooded the holds.

During action collision mats were dragged over the hole by men struggling up to their waists in water. Above the crash of gunfire and bursting bombs outside the men could hear from loud-speakers throughout the ship the calm and measured words of the chaplain, who was describing the battle. He stood on the exposed bridge with a microphone to his lips all that day, telling the men below what was happening. For the first time in naval warfare the engine room staff were given a minute-to-minute account of what was happening outside. The heroic chaplain was afterwards awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

At four in the afternoon another wave of dive-bombers attacked, and it was then that a direct hit on an octuple pom-pom killed the entire crew, blowing the bodies overboard. Immediately afterwards a large bomb penetrated the overhanging flight deck at the bows, ripping up the thick steel deck as though it were a tin can, leaving a vast hole with edges curling up like the petals of some fabulous flower. The design of aircraft carriers permits of little protection to the gun crews, but for six hours the heroic gunners remained at their stations. Though blackened by smoke and deaf from concussion, they fought back, firing from their high-angle A.A. guns thousands of rounds of 4.5 shell and pom-pom ammunition. A direct hit on a pom-pom station drove the body of one of the gunners through the deck. The enemy dived to the level of the flight deck and, sweeping along the full length of the ship in the face of terrific fire, machine-gunned the pom-pom stations, killing many of the crews.

Observers on other ships, appalled at the terrible battering Illustrious was getting, abandoned hope for her. Aircraft carriers, without the armored decks of battleships, are not built to withstand direct vertical hits, but Illustrious had received three such hits and still floated. She had also sustained several of those near-misses which, bursting in the water alongside, put a pressure on the hull that buckles the heaviest plating, and hurls jagged fragments of steel into the ship. Over a thousand such splinters, some making holes big enough for a man to crawl into, pierced the carrier’s sides, cutting and ripping through electric cables, voice pipes, and steam and water pipes, and killing members of the crew. A direct hit on the stern had put the steering gear out, and for the rest of the action she steered with her engines — that is to say, by the alternate use of her propellers. At times the 750-foot hull was completely hidden in clouds of smoke and fountains of spray. A photograph taken from the deck of a cruiser less than a mile away at the moment she received a direct hit shows nothing but a mushrooming cloud of smoke billowing darkly over the sea.

On board Illustrious the undaunted defenders of their ship were still manning the guns, still fighting the fires and the inrush of water below, removing the dead and attending to the wounded. The hospital deep in the interior of the ship was crowded with wounded men, and the surgeon and his assistants were working without rest in the sickening atmosphere of ether and cordite fumes. Wounded men lay on the decks in rows waiting their turn for emergency operations. Above on the island — the bridge and control-tower — Captain Boyd and his officers remained directing the ship. Many missed death by the narrowest margin of chance, but many lost their lives. The heavy bronze ship’s bell was perforated and ripped by shell fragments, till it resembled rat-eaten cheese, and the bride-island plating was holed in a hundred places. A bomb fragment weighing ten pounds pierced the control-tower, missing seven men stationed there. Though the gallant ship seemed to be taking all the punishment, she was making the enemy pay heavily for it. Her gunners are believed to have shot down nearly fifty of the attacking bombers, and at least one Stuka was blown to pieces by the upward blast of the bomb it had just dropped on the flight deck of the carrier. The fight of Illustrious, as bloody and brave as any in the history of the British Navy, can be compared to the fight of Sir Richard Grenville’s Revenge.

At half-past five, in the fading light, the enemy returned to make his last attack. About thirty-five Stukas roared down one after another to within a hundred feet before leveling off to drop their bombs, but so fierce was the anti-aircraft fire from Illustrious and other ships that, the enemy’s aim being persistently obstructed, the bombs fell wide and the battered ship escaped further damage. But she had had enough. In the savage all-day bombardments she had absorbed more punishment, still floating, than any ship in the war to that date. Her flight deck was torn up by four great jagged craters; her hangar deck was burned out and all her planes destroyed; her steering gear was disabled and her engine room in chaos. Her funnel and bridge-island superstructure were perforated with a hundred holes; searchlights, rail stanchions, steam pipes, Carley floats, ladders, and all the complicated mass of gear belonging to the superstructure were twisted and bent into a ghastly tangle of scrap steel. When the roll was called her casualties were found to be 14 officers and 107 men killed and over 400 wounded.

During the attack the convoy had scattered, though some of the escorting warships had remained with Illustrious and had not escaped damage. Although the enemy had failed to achieve their main purpose — to sink the carrier — they had put her out of action for months, and so damaged the 9000-ton cruiser Southampton that she be came a total loss. Heroic efforts were made to save her, on fire and out of control, but after hours of titanic effort the survivors of her crew were taken off and she was sunk by British forces. Most of the crew were saved.

Illustrious, though still afloat, was too badly hurt to continue at sea, and her captain decided to make under cover of darkness for the refuge of Malta, about 150 miles away. This naval base, close to enemy territory and subject to frequent bombing, was not an ideal sanctuary for the battered ship. Alexandria would have been far preferable, but Illustrious was in no condition to withstand the 1000 mile voyage, and so Malta was the inevitable choice, though the enemy was bound to find her there and make further attacks. The crippled ship, escorted by screening destroyers, limped into Valetta naval harbor the next morning.

At Valetta were well-equipped machine shops, heavy cranes, and everything necessary to carry out extensive repairs to the damaged carrier, but the enemy had no intention of permitting their victim to recover, and after a search of the Sicilian Channel they found her in the naval dock. Her dead and wounded had already been taken ashore, and scores of mechanics had invaded the ship to begin temporary repairs. Towering over her swung the giant crane ready to lift out damaged machinery and torn plating. The work had already begun when the first enemy planes, flying at a great height, came over. The sound of air raid sirens had scarcely died away when the first bombs fell. As usual in enemy raids on ports and dock yards, most of the bombs fell on the town, but some fell on the dockyard, one stick blowing up a row of warehouses and workshops close to Illustrious. Towering clouds of dark smoke rolled up from the town, and falling fragments of A.A. shells kicked up spurts of water on the sunlit harbor. The bombers, coming over in waves, roared across like angry hornets, twisting and climbing to avoid the A.A. fire from the harbor defences. The enemy’s aim was, under the circumstances, very good. Within the space of ten minutes bombs had hit the dock sheds, the dock, and the ship herself. The bomb that fell on the quay did some superficial damage to the ship from flying fragments, but a moment later a direct hit down the rear elevator hatch rocked the vast hull as in an earthquake, and caused further destruction to the interior of the already wrecked ‘tween decks.

After the enemy had gone and the new dead and wounded were removed it seemed as though Illustrious was damaged beyond hope of repair. The German pilots, seeing the direct hit, must have thought so, but with Teutonic thoroughness they came again and again. In two weeks Illustrious was attacked four times as she lay along side the dock at Valetta. The enemy caused wanton destruction in the town and considerable damage on the dock, but they failed to destroy Illustrious. They came over and took photographs, and when their expert annotators studied the results they had to admit that the ship was still upright, though she was certainly full of water and resting on the harbor bed. She could not conceivably be of any further use to the British Navy. Meanwhile down in the battered interior of the ship the engine room staff, ignoring the falling bombs, had struggled night and day to carry out temporary repairs. New sections were put in broken steam pipes, electric cables were spliced, the smashed steering gear repaired and steel plates riveted over the holes in the hull. Thus patched up, and with steam again in her boilers, she slipped out of the harbor under cover of night and put to sea under her own power on a course for Alexandria. It was the Navy’s only hope of saving the ship, but a hard choice, for the 1000-mile voyage for a crippled ship crawling along at half-speed in waters infested with enemy submarines was not a comforting alternative. But if Illustrious could get to the Egyptian base she would be comparatively safe, as it was too far from Axis airfields to be in any danger from heavy air raids.

Steaming eastward with an escorting destroyer screen, the wounded giant slowly crawled towards the sanctuary. She had got away from Malta in such secrecy that even the people of Valetta were surprised when they woke up and found her gone. So, too, was the enemy when one of his reconnaissance planes discovered the empty dock. When photographs disclosed that Illustrious had not sunk but had actually departed the Luftwaffe was ordered to find and destroy her. She could not have got far away in her crippled condition, nor were the enemy long in finding her. But she was well protected by escorts, and now, some hundreds of miles from Malta, she was slowly drawing out of effective bombing range. The enemy attacked her, but without the ferocious persistence of that dreadful day when they all but put an end to her career, and as she drew farther away from the land the attacks ceased, and she was permitted to reach Alexandria without any damage.

At once the dockyard repair gangs took her over and began further temporary repairs. Captain Boyd, who had brought Illustrious through her bloody ordeal, was promoted to the rank of Rear-Admiral, and he was succeeded in command by Captain G. Seymour Tuck, late executive officer of the ship. Meanwhile the British government, gratefully taking advantage of an agreement with the United States permitting ships of the Royal Navy to be repaired in American yards, was in touch with Washington about getting the damaged carrier repaired in a United States navy yard. While temporary repairs to her were being done at Alexandria her captain received orders to take her to Norfolk, Virginia, as soon as she was ready to put to sea. The route was, of course, a secret, as also was her departure from Alexandria. With her flight deck patched up, and a few planes for self-defense, she slipped out of the Egyptian port one morning in the early spring bound on her long and perilous voyage. Steaming at reduced speed, she turned east for Suez and the Red Sea, since the shorter voyage westward through the whole length of the Mediterranean would have been suicidal in the ship’s crippled condition. Through the Straits of Bab-el Mandeb (the Arab “Gate of Tears”) Illustrious turned eastward to Cape Guardafui and thence south along the coast of Somaliland and Portuguese East Africa to Cape Town. From there she limped up the South Atlantic to her destination, the great United States navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia, where she arrived in the middle of May 1941, four months after the bloody battle in the Sicilian Straits.

At Portsmouth navy yard American workmen began stripping out the damaged machinery and plating while her crew, with well-earned shore leave, fraternized with the hospitable people of Norfolk. The Americans gave them a wholehearted welcome. Three months after the arrival of the ship at Norfolk Captain Tuck, who had received the D.S.O. for his part in the battle, was promoted to a higher command, and Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten, who had commanded the torpedoed destroyer Kelly, took over the rebuilt carrier in a formal navy ceremony on the flight deck. In dazzling sunlight and in white tropical duck the surviving officers and crew watched Captain Tuck hand over his command to their new commander, the tall and handsome cousin of the King. The deafening clamor of riveting hammers and all the accompanying noises of the shipyard were stilled while the brief ceremony was carried out, and when this was over the work on the ship proceeded, for there was no time to lose. With the Royal Navy spread dangerously thin over the Seven Seas every ship was needed, and before the winter came Illustrious was at sea again and as good as new. The enemy had failed in his sworn resolve to sink the hated ship which was mainly responsible for the Italian disaster at Taranto….

5